Spruce Production and Northwest Labor Unrest

The 2100 miles of coastline from Oregon to Alaska is home to the Sitka spruce tree. Due to soil and precipitation, the Pacific Northwest facilitates the growth of spruce trees to heights in excess of 300 feet. With the success of the Wright Brothers, spruce found a use as wing spars for new airplanes because it is strong, lightweight, and straight.

In 1917, 50 timber companies owned half of the timberland in the Pacific Northwest. The workers, mostly foreign born, worked 10-11 hours a day at a low wage. Companies often relied on local and state governments to suppress union efforts to improve working conditions. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) Shingle Weavers Union was the first timber labor union, founded in 1903. Because many loggers were unskilled migrant laborers, they did not qualify for AFL representation and so turned to the Industrial Workers of the World for help.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is an international union that was founded in Chicago in 1905 by a coalition of radical trade unionists, anarchists, Marxists and socialists. IWW members--nicknamed "Wobblies" --were critics of the craft union organizing model and the business unionism embodied by the majority of the biggest labor federation in North America, the American Federation of Labor (AFL). While the IWW was successful in recruiting in many places throughout the country, its influence was most perhaps widespread in the Pacific Northwest, especially between 1910 and 1919.

The incident known as the Everett Massacre was a bloody confrontation that occurred when a boatload of IWW members attempted to land on an Everett dock. As the 300 IWW members arrived at Everett on the afternoon of November 5, 1916, they were met by a crowd of local police and over 200 armed and "deputized" citizen vigilantes. The IWW members had returned after IWW organizers had been run out of town and beaten by business owner vigilantes due to their support of an Everett shingle weavers' strike. The IWWs had returned to mount a "Free Speech Fight," a tactic in which the IWW would flood into a town to exercise their free speech rights, get arrested, and overwhelm the local jails and courts.

This tactic had proved successful in several other campaigns in different locales throughout the United States, sometimes establishing a precedent of non-harassment for public speaking by local authorities. After tense words between Snohomish County Sheriff McRae and the IWW members on the boat regarding whether they could land on the dock, a shot was fired. It is not clear which side fired first, since both sides were armed. However, it became clear that the Everett crowd was better armed in the ensuing ten-minute gunfight. The IWW boat almost capsized, dislodging IWW passengers into the water, some of whom were shot and some of whom probably drowned.

In the battle's aftermath, 5 IWW members were confirmed dead--though the number may have been as many as a dozen--and 27 were wounded. The dead Wobblies were: Hugo Gerlot, Abraham Rabinowitz, Gus Johnson, and John Looney were dead, and Felix Baran lay dying. Two citizen deputies were killed with 16-20 wounded, including the Snohomish County sheriff. Ironically, the two killed deputies were actually struck by "friendly fire" from their fellow deputies, who shot them in the back during the melee. Seventy-four IWW members were arrested upon their return to Seattle and put in the Snohomish County jail. Eventually all of the prisoners were released except for one IWW leader: Thomas Tracy. Tracy stood trial for the murder of the deputies—a crime for which he was ultimately acquitted.

In March 1917, the IWW formed the Lumber Workers Union Number 500 to control operations in the Pacific Northwest lumber industry. In June 1917, the IWW announced a general strike to occur on July 16 if their demands for an eight-hour work day were not met. To shut down the IWW, soldiers arrested union members and raided the union's Spokane headquarters on August 20, 1917, arresting more than 35 of the union's leaders. Running out of funds, and with their leaders in prison, the IWW instructed its workers to return to the job but to slow down work and execute small acts of sabotage.

The strike and work slowdown affected the flow of much-needed airplane lumber for the war effort, which concerned General Pershing as he prepared to leave for Europe in June 1917. Pershing suggested to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker that an Army office be assigned to assess the problem and report its observations to the War Department. General Pershing recruited Colonel Brice Disque, who had served under General Pershing in the Spanish-American War and was then Warden of the Michigan State Reformatory. Colonel Disque proposed that best solution to the lumber problem in the Pacific Northwest was to form an Army Service Division dedicated to supplying soldier-loggers to supplement civilian labor and to provide troops to suppress labor problems caused by the IWW. This division was to be the Spruce Production Division.

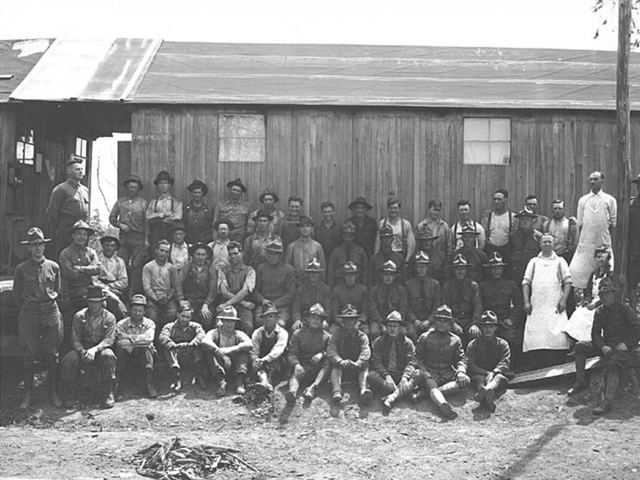

In October 1917 an association of employers and employees pledged to work together to produce spruce for the war effort. This association would not be part of the Spruce Production Division, but would take orders from its officers. This became the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (4L), chosen for its avoidance of the word 'union', which separated the 4L from the dissensions created by the IWW.

On November 26, 1917, the Spruce Production Division took the first step in forming the 4L by issuing Memorandum No. 1, which assigned recruiting officers to seven newly-formed labor districts. These officers were traveling representatives of the 4L, instructed to visit each logging camp and mill in their territory that produced spruce or fir lumber for airplanes and ships. They were to establish a 4L local, appoint a secretary, and enroll members at each location. The secretary was to report on the loyalty of the non-members in camps and on any acts of sabotage. New members of 4L were told that if they worked to increase lumber production, the Army would take care of their concerns about hours worked, wages, and living conditions. Workers who refused to sign the loyalty pledge were believed to be IWW members and were fired.

4L locals were established in Coos Bay, Tillamook, Astoria, Willapa Harbor, Gray Harbor, Seattle, and Bellingham. These districts were part of the Coast Division of the Loyal Legion. Later, locals were set up east of the Cascades. This division was called the Inland Empire Division, whose headquarters was established in Spokane, Washington. This division had ten districts: Yakima, Wenatchee, Spokane, Sandpoint, Coeur D'Alene, St. Maries, Potlach, Winchester, Kalispell, and Missoula. An eleventh district was established in late 1918 in Bend, Oregon. After the war, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen continued to support workers with social halls, annual conventions, and employment agencies, but membership gradually declined, and the 4L shut down in 1938.

The labor movement was under intense scrutiny, especially the IWW, who were pacifists and radically anti-war. Two women in Seattle faced scrutiny and jail time for their dissent. Louise Olivereau came to Seattle in 1915 to work for the IWW as a stenographer in the Wobblies' Seattle office. She became active in the anti-war movement in Seattle, worried about what she saw as a prohibition on inquiry and discussion that arose with politicians' desire to quell dissent and sedition during the war. City newspapers published weekly the names of men who had been conscripted, and Olivereau mailed each person flyers she wrote, urging them to become conscientious objectors. She was put on trial for sedition, found guilty, and sent to prison in Colorado.

Anna Louise Strong was a progressive journalist who also arrived in Seattle in 1915. An advocate for child welfare, she ran for the Seattle School Board in 1916 and won easily. That same year, she gained national prominence for her national reporting on the Everett Massacre. However, U.S. entry into the war in 1917 threatened her position on the school board. Along with the parent-teacher association and women's clubs throughout Seattle, she opposed military training in schools and was branded as unpatriotic for her anti-war beliefs and writings. She was also seen as a friend and supporter of Louise Olivereau, standing by her side during Olivereau's sedition trial. Strong was narrowly recalled from the school board. Along with her journalism, she wrote poems as a form of protest, including the poem "Who Killed Our University?" about Suzzallo.

Groups were actively involved in keeping track of the Wobblies, such as the American Protective Legion, or "the Men Behind the Government" as they called themselves. As stated in its Seattle charter, "it is the purpose of this organization in our community to relieve the Government of the preliminary work necessary in collecting, and making an investigation of, any and all cases which appear to be infractions of Federal, or State laws, of whatsoever name or nature and to collect and reduce the facts to a point ready for prosecution by the proper authorities." The organization kept a watchful eye on IWW activities. In a summary of activities, "we are now handling a number of cases from murder to slackers. Have listed and have reports upon 1100 dangerous I.W.W. and 8000 others. Have arranged for advice on movements of I.W.W. coming here (Seattle) from mining camps of the Rockies."

At the end of the war, unions in Seattle's shipbuilding industry demanded increased wages. The industry, in an attempt to divide the unions, offered a wage increase only to skilled workers. As a result, shipbuilders went on strike on January 21, 1919. On February 6, in solidarity with the striking shipbuilders, a general strike of all workers was called for, in an incident known as the Seattle General Strike. Recently returned war veterans among the strikers wore their uniforms for the event. The city of Seattle was effectively paralyzed for five days, until Mayor Ole Hanson called on a large force made up of federal troops, police, and deputized citizens to end the strike.

Later that year, on November 11, Armistice Day, a parade in Centralia, Washington was interrupted by a riot that resulted in gunfire, killing four veterans recently returned from the war in an incident that is now known as the Centralia Massacre. A rumor had circulated that the IWW hall would be attacked during the parade. As a result, IWW workers were armed to defend their rights and property. When the parade stopped in front of the IWW hall, the hall was attacked by ex-servicemen organized under the American Legion. The armed IWW members fired on their attackers from inside the hall and from a hillside nearby. Several of the attacking servicemen were killed or injured. Wesley Everest, one of the armed IWW members defending the hall, ran out the back as he was being chased by the attackers. He shot three of them, and killed at least one of them. For his actions he was jailed, and later lynched. Other IWW members were later accused of murder in this case and sent to prison.