Influenza Pandemic

I had a little bird, its name was Enza. I opened the window, and in-flu-enza.

The "Spanish Flu" was the most devastating pandemic in recorded history. So-called because the first reported deaths out of heavily censored Europe were from neutral Spain, the flu rapidly spread worldwide as soldiers began returning home. An estimated 21 million people died globally, including more than 700,000 in the United States.

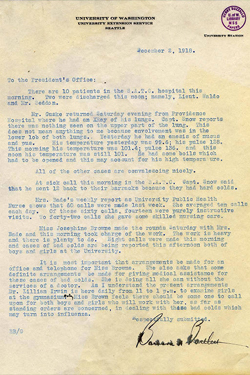

On October 3, 1918, the epidemic arrived in Seattle, with 700 cases and one death reported at the UW's Naval Training Station. A trainload of already-ill troops had arrived in Seattle from Philadelphia headed for Camp Lewis and Camp Lawton. The virus spread rapidly. Over the next six months, more than 1,600 people died, most between ages 20 and 35, despite the closing of churches, theaters, and schools. Public gatherings were prohibited, and six-ply gauze masks were mandated. At the UW, the Women's Dormitory (now Clark Hall) served as a make-shift hospital for campus cases.

Because the disease appeared in Seattle six weeks after it was first seen in East Coast cities, local officials had time to plan to contain the disease. A vaccine was developed quickly, and over 10,000 shipyard workers at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard were ordered to be vaccinated. None developed influenza.

Despite the public health restrictions, local compliance immediately eroded when Armistice was announced on November 11, 1918. Joyous Seattleites took to the streets in celebration. The mask rule was lifted the next day, and public places reopened. New cases were immediate, and deaths climbed again, peaking on December 9, 1918. Schools reopened in January, and by March no deaths had been reported. Because of its advance public health measures, Seattle had a death rate roughly half that of San Francisco and a third of rates in Philadelphia and Baltimore. The Spanish Flu disappeared almost quickly as it appeared and has yet to reappear with such intensity.