Sedition and Dissent

"This was in the spring of 1917. I took a year's leave of absence in the fall, for the reason that I had been raised in a German family, and this was a witch-hunting period. That was a favorite sport of a good many people. I didn't believe that the war was fought for democracy, as many did; I could see an economic motive. In fact, I am always looking for an economic motive, no matter what war it is. I came from a German home, and I knew that the wisest thing for me to do was to take a year off, so I left the campus and went to New York, and did some research work while there"

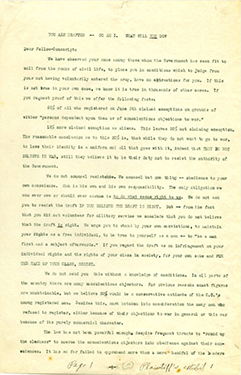

Even before the U.S. officially entered the war, people were suspicious and nervous of German-born citizens and "hyphen Americans," meaning anyone foreign born or non-assimilated. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Suzzallo started volunteer secret services for UW and the State Council of Defense. Volunteers were instructed to look out for "all members of German birth and dissent."

"I have three unusual opportunities to keep watch:

- As soon as the war broke out I asked the Federal Secret Service to watch all men in the German Department and all persons of German birth and descent… I have constant reports from them and am acting upon their advice.

- As Director of the State Council of Defense I have access to all reports of the state and volunteer service, which are constantly coming to my attention.

- … there is a volunteer service organized within the University of Washington itself"

The first victim of this was Fredrick Meisnest, a long-time faculty member and head of the German department. In a talk entitled "Germany is Faust, not Hamlet," which had been scheduled before U.S. entry into the war, Meisnest spoke on the character of Germany and why he believed the country deserved sympathy. Letters poured in, both demanding Meisnest's removal and writing in his support. Suzzallo convened a faculty committee to determine whether treason had been committed. The committee found that the talk was not treasonous or seditious but was ill-timed and should have been cancelled. He was first removed from his position as head of the department and then ultimately resigned. The German department faced precipitous drops in enrollment, and by the end of the war there were only three faculty left. Meisnest was re-installed in his position in 1927, after Suzzallo was fired.

As the war was coming to an end, tensions and fears of sedition remained high on campus. In October 1918, when the first SATC troops were settling in on campus, there were three incidents of food poisoning that affected 600 SATC members. Fervor on campus peaked around the belief that a mess hall worker, Jessie Rothges, poisoned the SATC troops. She was engaged to a German-American and hadn't paid her Liberty loans, which many considered conclusive evidence. However, it was discovered that in the haste of setting up campus for the SATC, the mess hall's refrigeration was constructed poorly, and that had caused the fish to go bad.