The Avant-Garde Picture Book: Introduction

The remarkable collaboration between Marshak and Lebedev began in 1925, when they created two of their most famous works, The Circus and Ice Cream. These two books together embody the beginning of a radically new approach to children's book design. Perhaps ironically, despite the enormous divide between these avant-garde Soviet books and the lavish ornamentation of pre-revolutionary books by Benois and Bilibin, a common element is the artist's emphasis on the book as a complete unity. Lebedev conceived of the children's book "as an artistic whole in which the elements are linked by a constructive unit." His masterpieces, such as The Circus and Ice Cream, "brilliantly expressed this constructional principle" (Kovtun 1996b, 217). Lebedev himself declared: "Every element [of the book] must be subordinated to the unified, overall composition" that supports the artist's vision (1933).

Lebedev's illustrations for his books with Marshak in the 1920s are particularly effective in their application of diverse avant-garde techniques to the children's book. Flattened, abstracted planes and geometrical shapes evoke the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich, but are adapted to a new Soviet reality. Rosenfeld has noted that this side of Lebedev's achievement recalls the mélange of Suprematism and Constructivism found in El Lissitzky's groundbreaking children's book, About Two Squares (1922), which combines the diagonal and architectural emphasis of Constructivism with the abstract "planar rhythms" of Suprematism (2003, 174–93). As Railing puts it, in this work El Lissitzky achieves a "suprematism of typography" (1991, 38).

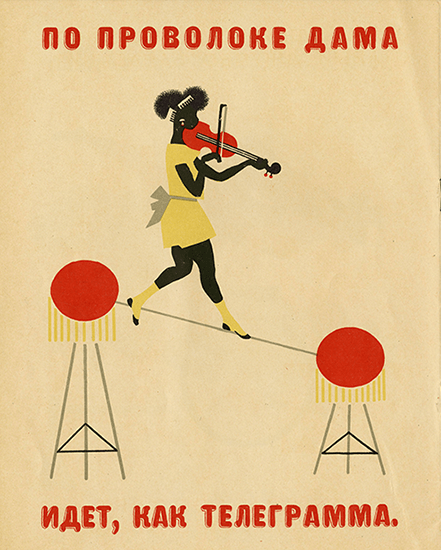

Lady on a Wire: The Circus

The Circus (Tsirk, 1925), the first collaboration between Marshak and Lebedev, is often cited as one of their most innovative achievements. As is the case for most of their collaborations, the text is in rhymed verse. Marshak later recalled that Lebedev first created the drawings, while Marshak wrote the text afterwards to accompany them: "For Circus . . . I wrote poems that were like signatures to Lebedev's drawings" (1968–72, 1:513). Lebedev is known to have had a special interest in the Leningrad circus; he often sketched circus performers during rehearsals (Rosenfeld 2003, 208). The relationship between image and text is particularly vibrant in The Circus: Marshak's "witty lines" play an important role in the visual composition of each page, "framing the lithographs from above and below" and endowing each page with vital equilibrium (Fomin 2009b, 2:13).

Page 6 of The Circus contains the line often praised by the famous Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. Translated with literal word order, it reads: "Along the wire the lady / Walks like a telegram." The playful rhyme of "lady" (dáma) and "telegram" (telegrámma) provides a bouncy accompaniment to the brightly colored geometric shapes of Lebedev's illustration. Both image and text advertise their rapid modernity: Marshak's choice of the word "telegram" heightens the sensation of speed, as does Lebedev's image of the slender wire, a dynamic diagonal line zipping down the page from one red circle to the other. The tightrope walker is balanced with precarious symmetry between two red balls teetering atop spindly triangular stands, which also evoke modernity in their resemblance to radio towers. Image and text intersect here in that the balls function as gargantuan punctuation points, marking the start and finish of the circus-lady's journey, while also echoing the period that ends Marshak's text. This book also exemplifies Lebedev's vibrant use of color. As Lebedev himself later said: "Color illustrations should be intensely colorful as well as precise and concrete. But the intensity should come not from gaudiness, but from the painterly composition" (1933). The bold red palette of this page (in both image and text) evokes the Russian lubo and the Russian icon, both of which privileged the color red along with other bright hues (White 1988, 5; Alekseeva 1996, 11).

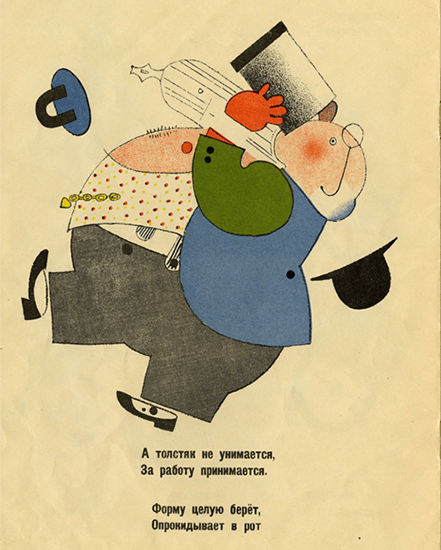

The Capitalist Fat Man & the Children's Collective: Ice Cream

While containing innovative visual designs that evoke both Constructivism and Suprematism, Marshak and Lebedev's collaborative works also point to the ideological concerns of their era. Ice Cream (Morozhenoe, 1925), for instance, juxtaposes a group of children longing for ice cream with a gluttonous fat man, who represents the overbearing capitalist, as was the case in numerous works in that era (Weld 2018, 98–107). Page 8 of this book shows the fat man exploding with greed: "But the fat man doesn't stop, / He gets right down to work. / Grabbing an entire cup, / He tosses it down his throat." The details of his clothing, such as his gold watch chain and spats, underscore his symbolic embodiment of bourgeois, capitalist wealth. He is so unable to contain his unbridled greed that he eats up all the ice cream and turns into an enormous snowdrift.

Weld notes that, alongside the contemporary Soviet context of this poem, the gluttonous fat man also evokes a medieval carnivalesque ritual in which the "clown disguised as king" is dethroned by a "victorious collective of children," which "restores order and justice to the world" (2018, 100–104). Many scholars suggest that the fat man represents not only the greedy bourgeoisie in a general sense, but also the Soviet NEP-men, i.e. capitalist entrepreneurs who took advantage of Lenin's New Economic Policy in the 1920s (Rosenfeld 1999b, 176; Hellman 2008, 222). Yet Fomin persuasively argues that the fat man in Ice Cream still contains a "pithy expressiveness," his metamorphosis from man to snowdrift driving the plot in a way that is "not just amusing, but also poignant" (2009b, 2:13).

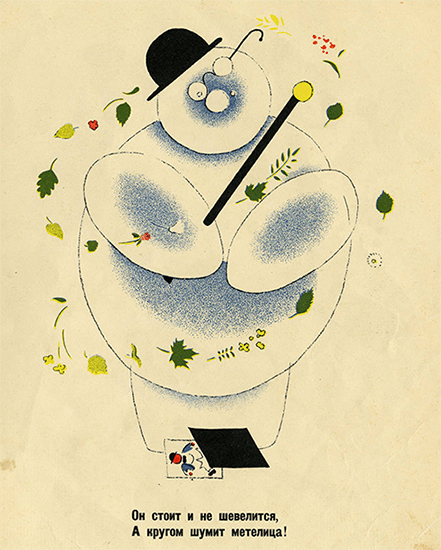

In fact, on page 11, the fat man, now a snowman in harmony with nature, is depicted with a gleefulness that seems more whimsical than vindictive. Both text and images are playful, with Lebedev's leaves and flowers gently swirling in the breeze around the snowman, whose glasses are now humorously askew, while Marshak's lighthearted text emphasizes the almost four-syllable rhyme of shevelitsiá (budge) and metelitsá (snowstorm): "He stands and doesn't budge, / While all around, a snowstorm howls!" At the same time, this book powerfully exemplifies Lebedev's adaptation of avant-garde techniques to the children's book. Many of the characters are depicted with schematized, geometric forms that evoke both Malevich's Suprematist shapes and Lebedev's own posters for the ROSTA Windows. Rosenfeld also suggests that Lebedev's faceless human figures recall the "robot-like figurines" that El Lissitzky created for a version of the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun, produced by Malevich's followers in 1920 (2003, 211).

The Poetry of the Past & Brightness of the Future: Yesterday and Today

Ideological concerns, and the relation between image and text, become particularly complex in Yesterday and Today (Vchera i segodnia, 1925), which juxtaposes old objects and customs with twentieth-century inventions. Intriguingly, there is a disconnect between the message of this book and its actual effect. While Lebedev's bold cover declares its sympathy for the side of the new, with its line of bent, aged figures carrying outdated objects, contrasted to young, strong figures heralding the new things, one can observe a tension between the soulfulness of Marshak's text (suggesting a sympathy with the antiquated, no-longer-needed objects) and the modern optimism of Lebedev's illustrations. In Marshak's autobiography of his early childhood, he remarks on some of the objects of this poem with tender poignancy, suggesting that the transition from old to new was not always straightforward: "Nearly all my childhood was spent by the light of a kerosene lamp . . . Those years marked the junction between the last century and the present one. The past was still fully alive, and did not seem to be making ready to cede to the new" (1964, 40).

Indeed, this tension between old and new is not only located in the text; even in Lebedev's illustrations one finds a contradiction between the supposedly antiquated technology and the poetic sympathy underlying its depiction. On page 1, several of the main "characters" are introduced: "Kerosene Lamp, Stearin-Wax Candle; Yoke with Bucket; Inkwell with Fountain Pen"; notably, this initial introduction of the main objects of the book focuses on the "old" rather than the "new." Yet, perhaps some irony lies in the contrast between the antiquated archaism that these objects represent and the extreme modernity of their artistic depiction. They float in a field of bright blue, unanchored by context or a mimetic frame. Steiner has noted that, for avant-garde artists of this era, "aesthetic mastery of the world was a mastery of things" and thus they divorce objects from their context, positioning them instead "on the white field of a page, in a neutral display window" (1999, 151–52). In this case, the antiquated, overbearing yoke, a symbol of peasant oppression, anchors the page with a rainbow-like curve. Meanwhile, the trim horizontal stripe of the fountain pen is answered geometrically by the elegant vertical wick of the candle. At the very center, the inkwell, rather than representing a dusty past, seems like a modern, geometrically schematic object, its top represented by a perfect sphere that is jumping towards the side of the page with an unhampered glee.

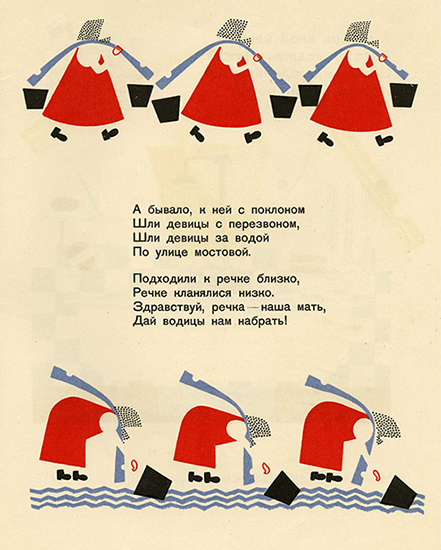

Even more striking is the contrast between the past and the present on pages 11–12, which juxtapose an image of young girls fetching and carrying water from the river with an image of a young "lout" (nevezha) using a faucet with running water. On page 11, the repeated image of girls from the olden days creates a rhythmic, visual pattern, like a Greek chorus commenting on the text. They are flattened and stylized, without any facial features, their heads rendered as pointillist dots that evoke the silhouette of their kerchiefs, their feet mere shapes kept at a distance from the rest of their bodies. Overall this page evokes posters and textile patterns of the Soviet era. Rosenfeld likens these images to Suetin's Suprematist compositions (2003, 212), and also argues that they evoke the tradition of Russian folk art: the "row of young Russian peasant women with water-carrying yokes resembles an ornamental border on peasant's embroidery" (245). Yet, in this simplified, "Suprematist" depiction of young women going to the river, Lebedev creates a visual poetry that is deeply sympathetic to them; they seem as alive and resonant, if not more so, than the "lout" using water from his bathroom sink on page 12. The text on page 11 heightens this perception: "In the old days, the girls walked to the river . . . along the cobblestone road." When they arrive at the river, they bow down low to her and greet her as they would Mother Nature: "Hello Mother River / Let us draw water from you." Nothing in either text or illustration undermines the poetically intense connection between the young girls and Mother River, whereas the lout washing himself at the sink seems both silly and pompous.

More ...

For more information on Marshak and Lebedev, read these essays: "The Soviet Production Book" and "The Five-Year Plan & the End of the Avant-Garde Picture Book".

View examples of Lebedev's works in the Harer Collection »

View examples of Marshak’s works in the Harer Collection »

View examples of books created by Marshak and Lebedev as a team »