"In graphic art at the beginning of the twentieth century . . . we [cultivated] the line in itself . . . and a strict decorative-linear discipline, . . . as found in Renaissance woodcuts, Japanese art, and ancient Russian art . . . when the master's relation to each line had to be precise, attentive, and sparing" (Bilibin, quoted in Golynets 1988, 9–10).

Ivan Bilibin & the Neo-Russian Style

Ivan Bilibin (1876–1942) began contributing to the journal Mir iskusstva (The World of Art) in 1899, and joined the group in 1900. He later credited this group for introducing him to Western art: "I learned a great deal from Mir Iskusstva . . . The pages of the journal were like a 'window on Europe' for me" (Bilibin 1970, 59).

Like the artists of Western Art Nouveau and its Russian embodiment in Mir Iskusstva, Bilibin was intensely interested in the notion of the "line." He later said that he believed in the "supremacy of the line" and the "linear techniques of the past" (quoted in Golynets 1981, 9). He also shared with other artists of his time a fascination with Japanese woodblock prints and the graphic design of Western artists, such as William Morris, Walter Crane, and Aubrey Beardsley (Verizhnikova 2001, 20–24).

In this sense, Bilibin's work reflects the tendencies of Art Nouveau, yet Bilibin forged his own distinct path. Unlike the Westernizing faction of Mir Iskusstva, discussed in the previous essay, Bilibin's aesthetic emphasis was on the more ancient culture of Muscovite Russia, dating to the seventeenth century and earlier, which preceded the Westernization of Peter the Great. In this sense Bilibin followed in the footsteps of the Abramtsevo Circle and Vasnetstov's Neo-Russian style. Bilibin was "enraptured by the decorative effect of small-scale patterns, . . . the bright coloring characteristic of seventeenth-century Russian art" (Golynets 1981, 8).

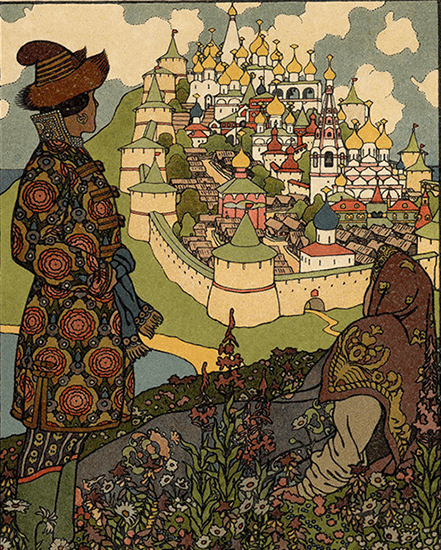

Bilibin pursued his interest in Old Russia very assiduously, conducting ethnographic trips (1902–1904) to Northern Russia, where he took photographs of Old Russian architecture, researched local crafts, and collected folkloric artifacts and "objects of everyday peasant life" (Golynets 1981, 8). After his journeys to the North, he wrote: "Just like America, ancient, artistic Russia [Rus'] has recently been discovered, . . . covered with dust and mildew. But beneath the dust she was so beautiful that the cry of those discovering her makes perfect sense: Return! Return!" (Bilibin 1970, 44). He was also particularly drawn to traditional Russian clothing, as can be seen, for instance, in his illustrations for Tsar Saltan, pages 9 and 11. He later said: "Russian people loved their clothing and filled it with poetry . . . Russian dress is the dress of peacefulness" (1909, in Bilibin 1970, 47–48).

Bilibin: Book Design as "Vocation"

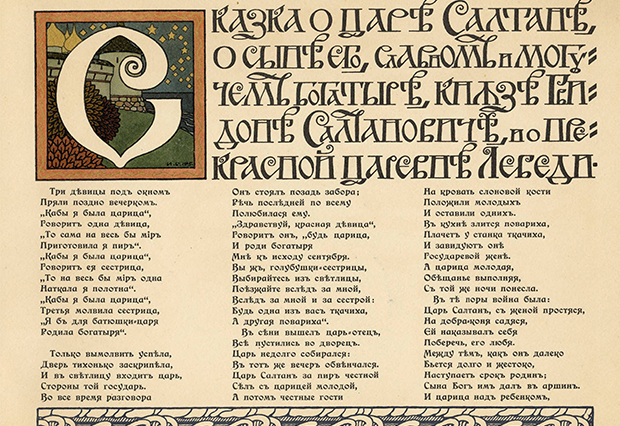

As we saw in the works for children created by Alexandre Benois and Walter Crane, Bilibin also emphasized the book as an integrated work of art, and aimed to merge all components (cover, vignettes, typography) into a complete unity. One could argue that Bilibin's fascination with the symmetry of Old Russian architecture is reflected in his notion of book design: in his essay on Northern Russia, he wrote that "the main principle in old Russian wooden architecture is that the detail should never drown the whole" and he admired the "balance between the overall outline and detail." Bilibin also likened architectural details to the elements of a book, comparing the decoration on the church at Kizhi to "a pretty vignette at the end of the text" (1904, in Golynets 1981, 184).

While many of his contemporaries focused on graphic design, Bilibin approached this realm with particular intensity. Golynets argues that, unlike other artists, Bilibin viewed book illustration as a "separate art form" and a "vocation," not just a sideline (1981, 6). "He helped establish a new approach to the book, where . . . everything, from the cover to the last tail-piece, is subordinated to a single artistic concept" (Golynets 1981, 15). Bilibin was particularly attentive to the design of book covers, title pages, stylized typography, border decorations, and vignettes (Jackson 2007, 45; Golynets 1981, 14–15). "Bilibin was singular in devoting his energies to lifting the book as art object to higher realms . . . His ability to conceive the overall vision of the completed object, rather than place images alongside appropriate section of text as 'illustrations,' was unrivalled" (Jackson 2007, 45).

Pushkin's Fairytales

One of Bilibin's masterpieces is his illustrated version of Pushkin's Tale of Tsar Saltan (Skazka o tsare Saltane, this edition 1905; Pushkin's work originally published 1831). Golynets notes that Bilibin's version of Tsar Saltan is "a consummate expression of Bilibin's love for the art of seventeenth-century Russia" and that "Bilibin's illustrations to the great poet's tales rank among the best" (1981, 10 & 12).

Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), the most beloved figure in Russian literature, approached the fairytale genre in his own idiosyncratic way with his fairytales in verse, the Skazki (Fairytales or Tales). Many of his contemporaries did not appreciate his efforts, perhaps because his tales did not fit some of the Romantic stereotypes. Unlike many Romantics, Pushkin didn't indulge in archaic or folk elements for their own sake, instead employing them in the service of a rich imaginative landscape. While the motifs and elements of the Skazki have their roots in both Russian and Western European folktales, as well as in lubki (illustrated broadsides) and in the tales that Pushkin's nanny told him as a child, they are not just adaptations of those sources, but rather are completely original works (Slonimskii 1976, 235–36; Gorodetskii 1966, 437–39). Pushkin wrote six Skazki, from 1830–34, but the masterpiece amongst them is the Tale of Tsar Saltan (1831). "Tsar Saltan is a perfect lyrical masterpiece, the most formally beautiful of [the Skazki], and the one that most sustains throughout the length of the tale the atmosphere and taste of magic" (Bayley 1971, 53).

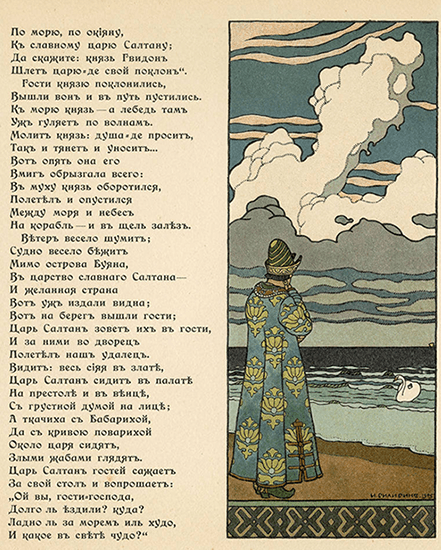

Prince Gvidon and the Cloud

Unlike many traditional fairytales, Pushkin's Tsar Saltan focuses not on formulaic or magical plot elements, but on vivid external details and the hero's mercurial emotional state. Underscoring the predominance of psychology over sorcery is the fact that Prince Gvidon's dilemma (his desire for a reunion with his father) is resolved not magically, but through his father's own decision to finally ignore his meddlesome advisors. More individualized than stock fairytale characters, Prince Gvidon is characterized through repeated lyrical passages in which he gazes at the sea and interacts with the Swan Princess, his pensive mood framed by concise, rhythmic images of the waves. Bilibin captures this repeated motif of the melancholy prince in his illustration on page 13, with Prince Gvidon's mood reflected in the enormous cloud overhead, which bursts with energetic swirls and dominates the landscape as if it were a persona in its own right, dwarfing the tiny swan in the corner of the frame.

Bilibin's visual treatment of the cloud, in fact, evokes Pushkin's own approach to landscape elsewhere in the poem, which is granted more tangibility and dynamism than often found in traditional fairytales. The wave, in particular, joins the action and is imbued with as much personality as the human characters: "Wave, my wave! / You are so free and wandering / You splash where you wish, / You sharpen the stones of the sea."

A Japanese Wave with Russian Ornament

Bilibin's illustrations evoke the centrality of the wave image in Pushkin's poem by twice making it the centerpiece of the page (pages 8 & 10). Bilibin's illustration on page 8 highlights one of the famous moments of the poem: young Prince Gvidon and his mother traveling the sea while trapped in a barrel. This passage exemplifies Pushkin's terse syntax and rhythmic musicality, which frames the characters' stark dilemma against the laconic simplicity of the surrounding landscape: "A storm-cloud travels across the sky / The barrel swims across the sea (Túcha pó nebé idyót / Bóchka pó moryú plyvyót"). As Samuil Marshak aptly noted, "The absence of other details makes the sky and ocean seem enormous, each occupying an entire line" (1968–72, 7:8).

Here Bilibin endows Pushkin's wave with both dynamism and delicacy: its ebullient energy recalls woodcuts by the Japanese artist Hokusai, while its ornamental border evokes Russian folk art (Golynets 1981, 10; Rosenfeld 2014, 180). Bilibin's book design thus reflects his eclectic mélange of sources. In her memoirs, Bilibin's first wife, Renee O'Connell-Mikhailovskaya (who was originally his student), later recalled the diversity of Bilibin's interests:

"He taught us to understand the creative work of such masters of drawing as Dürer, Cranach, Valloton, and Beardsley . . . He showed us Japanese engravings by Hiroshige, Utamaro, and Hokusai. Among them there were views of Mount Fujiyama by Hokusai . . . He taught us to understand and love Russian folk art . . . He told us that the Byzantine artists fasted and prayed before setting about their work and that we should do the same" (quoted in Golynets 1981, 192).