Introduction

The collaboration between Samuil Marshak (1887–1964) and Vladimir Lebedev (1891–1967) looms large as one of the most innovative collaborations in the history of children's books. Their works comprise the bulk of the Pamela Harer Collection of Russian Children's Books, which includes about thirty books either authored by Marshak or illustrated by Lebedev (approximately fifty books if one includes multiple editions, of which the Harer Collection has a rich array), and fifteen titles written by them as a team. A portion of these have been digitized and are available online in this exhibit. Many of the seminal masterworks created by the Marshak–Lebedev team were published by Raduga ("The Rainbow"), a renowned Soviet publishing house that was founded in 1922 by Lev Kliachko, and then shut down by the government in 1930. In the years 1925–27 alone, together Marshak and Lebedev produced at least seven books for Raduga, including masterworks such as Ice Cream (1925), Circus (1925), Yesterday and Today (1925), Baggage (1926), and How a Plane Made a Plane (1927).

Both Marshak and Lebedev were exceptionally sensitive to the child's perspective of the world. Marshak later declared that, for a child, "the most humdrum details of everyday life are . . . events of enormous significance." He also noted the way words and sounds have particular importance to children: "The attitude of children to words . . . is far more serious and trustful than that of grown-ups. They expect any combination of sounds to follow some kind of pattern" (1964, 26–28). Lebedev similarly saw a connection to early childhood perception as essential to his art: "An artist working on a children's book must be able to access that feeling of excitement that he experienced in childhood. When I work on a book for children, I try to recall the perception of the world that I had as a child" (1933).

Biographical Background: Samuil Marshak

Samuil Marshak has been called "the Russian Lewis Carroll" (Marshak 1964, 12). He was born in Voronezh, spent much of his childhood in and near Ostrogozhsk, and moved to St. Petersburg as a teenager. In the 1910s, Marshak spent two years as a foreign correspondent in England, and discovered British poets such as Wordsworth, Browning, and Lewis Carroll, as well as the rich tradition of English nursery rhymes, which proved to be very significant to his development as a writer. Marshak began translating English poetry and writing poetry for children while in England. He later described his discovery of English children's literature while attending classes at the University of London: "Above all, it was the university library that taught me to love English poetry. In those crowded . . . rooms, whose windows looked out over . . . the barges of the Thames, I first . . . stumbled upon English children's folklore, marvelous and full of whimsical humor" (Marshak 1968–72, 1:9).

Sounds and rhythms were an essential ingredient of Marshak's relation to language and verse. As he later recounted in his autobiography: "I was 'writing poetry' before I learned to write. I used to make up couplets, and even quatrains, orally, to myself . . . Gradually this 'oral tradition' was replaced by written verse" (1964, 135–36). In the 1920s, Marshak became a dominant figure in children's literature in Leningrad. He published his first poems for children in 1923, and started collaborating with a new magazine for children, The Sparrow (Vorobei, 1923–24), later renamed The New Robinson (Novyi Robinson, 1924–25). (Biographical details from Hellman 2013, 318–20; Marshak 1964; Sokol 1984, 94–98. For a discussion of Marshak's "mythologization" of his own childhood in his autobiography, see Balina 2008a.)

Biographical Background: Vladimir Lebedev

Vladimir Lebedev is widely regarded as the preeminent Soviet designer of children's books in the 1920s. He was born and raised in St. Petersburg, began drawing as a child, and published his first artworks in journals as a teenager. His roots were in satirical illustration: he published numerous caricatures in satirical magazines both before and after the revolution. In 1912, Lebedev began studying at both the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts and the private studio of Mikhail Bernshtein. (Biographical details from Petrov 1971; Rosenfeld 2003, 199–216; White 1988, 84–88.)

Although Lebedev was acquainted with many members of the radical avant-garde in the 1910s and 1920s, and was influenced by diverse sources such as Russian folk art, lubki, Cubism, Suprematism, and Constructivism, he never officially joined any of the artistic circles of the day and developed his own path. Lebedev later said that he considered himself "an artist of the 1920s": "I created my best works then . . . The roots of all my ideas grew from that era . . . and the language of my art was Cubism." Yet Lebedev adapted Cubism to his own individual style: "I'm not an imitator; I start with nature and my own understanding of the world, and my Cubism does not resemble the Cubism formulated by the theoreticians" (quoted in Petrov 1971, 248).

Vladimir Lebedev & the ROSTA Window Posters

In the early 1920s Lebedev became one of most significant and innovative artists of the so-called "ROSTA Windows," which were not windows at all, but rather posters displayed in the windows of empty shops and in other busy urban places such as train stations and bridges. ROSTA was the acronym of the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSsiiskogo Telegrafnogo Agentstva), "a syndicate of the Soviet press" (White 1988, 65), which collected news items by telegraph, and then distributed this information via published daily bulletins, wall-newspapers, and posters. The ROSTA window posters first originated in Moscow, in Autumn 1919, where they were mostly created by Mikhail Cheremnykh and the Russian Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. Soon after, a ROSTA Window Poster department was established in Petrograd in April 1920, headed by Vladimir Kozinsky (1891–1967) and Vladimir Lebedev. Lebedev created about six hundred posters although only about one hundred survive to this day. Unlike the cardboard-stencil technique of the Moscow ROSTA posters, the Petrograd artists used linoleum engraving. White argues that the Petrograd posters were "livelier in form and richer in content" than in Moscow, and they were also much larger in scope, so as to fit the Petrograd shop windows (1988, 81–89).

Vladimir Lebedev is widely considered to be the most important of the Petrograd ROSTA artists, and his posters were more actively engaged with avant-garde trends such as Cubism and Suprematism (Barkhatova 1999, 137; White 1988, 81–89). Lebedev was also notable for the extreme speed at which he could work: "On receiving the latest telegram from the front or elsewhere, the theme for each Window would be chosen immediately . . . Lebedev was able to produce an engraving in only seven minutes . . . Otherwise there was a risk that the poster might be out of date by the time it had appeared" (White 1988, 85).

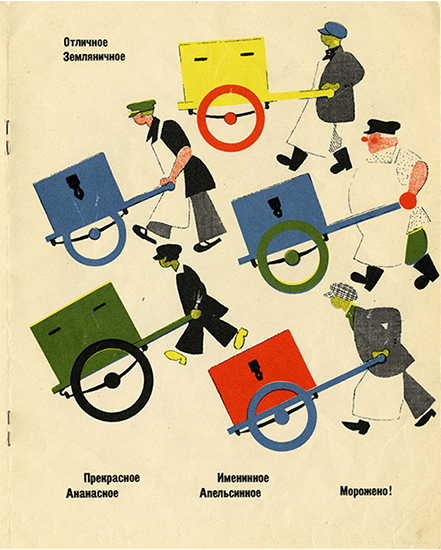

Lebedev's work for the ROSTA Window posters laid the groundwork for some of his most innovative children's book designs. In Ice Cream (Morozhenoe, 1925), for instance, on page 7 he depicts the collection of ice cream vendors as a repeated pattern of identical figures, which evokes not only Suprematism, but also Lebedev's own ROSTA posters such as You Must Work with Your Rifle Beside You (Rabotat' nado, vintovka riadom, 1920) and Peasant, If You Don't Want to Feed the Landlord, Feed the Front (Krest'ianin, esli ty ne khochesh' kormit' pomeshchika, nakormi front, 1920) (White 1988, 86). As in the ROSTA posters, the ice cream vendors in Ice Cream are schematized and geometrical, their faces flat and featureless, their ice cream carts forming colorful diagonals across the page, while Marshak's text celebrates the treat with a series of rhyming adjectives: "Delicious / Wild Strawberry / Beautiful / Pineapple / Birthday / Orange / Ice cream!"

Shortly after his work with the ROSTA agency, Lebedev made a great splash in the world of children's book design with his two early children's books published in 1922, The Elephant's Child (Slonenok) and The Adventures of Scarecrow (Prikliucheniia Chuch-lo), which were widely admired for their innovative application of avant-garde methods to children's illustration. In Lebedev's "pathbreaking" Elephant's Child, he deconstructed the animal figures into "simplified geometric components and monochromatic fields of color" (Weld 2018, 53). Steiner links these images to Cubism, Suprematism, and Constructivism, and notes that these "Cubist constructions . . . made an enormous aesthetic impression on Lebedev's contemporaries as well as generations of critics to come" (1999, 43). Lebedev's artwork and handwritten lettering in Scarecrow, on the other hand, evoke the Neo-Primitivist, Cubo-Futurist books of 1912–13 by Aleksei Kruchenykh, Mikhail Larionov, Natalya Goncharova, and others, as discussed in the essay on the lubok.

Marshak-Lebedev Collaboration at the State Publishing House (Gosizdat)

Together Marshak and Lebedev not only created a new style and visual vocabulary for the picture book in the 1920s, but also served as beloved mentors to an entire generation of artists and writers, who are often collectively referred to as the "Leningrad School of Children's Books" or "the Lebedev School" (Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 113–15; Rosenfeld 1999b, 170). In 1924, Marshak and Lebedev took charge of the Leningrad division of the new Children's Literature Department (Detotdel) of the State Publishing House (Gosizdat, or GIZ), which was located atop the famous Singer Building on Nevsky Prospect. Marshak was the literary editor, Lebedev was the artistic director, and together they worked with and nurtured an outstanding cadre of writers and artists, such as Vitaly Bianki, Boris Zhitkov, Evgeny Charushin, Vladimir Konashevich, Vera Yermolaeva, and Mikhail Tsekhanovsky. Many sources refer to this seminal publishing house of the 1920s as "Detgiz," although Detgiz per se was not officially established as a publishing house until the 1930s. Regardless, the term "Detgiz" has often served as an informal designation for the 1920s operation.

Marshak was known as a legendary editor, remembered later with great fondness by those he mentored: "Marshak united us; he was the center around which everything turned . . . His editorial work was not a craft but an art . . . In that process there occurred the miraculous birth not only of the book, but of the author himself" (Isai Rakhtanov 1971, quoted in Sokol 1984, 98). Lebedev was also remembered as an outstanding and exacting mentor to other artists. He corrected their drawings "with great passion and persistence," and insisted that they learn the technical side of book production: "He required that the artist himself transfer his drawing to a lithographic stone rather than leaving this task to the printer." Yet Lebedev did not impose his own artistic views, instead "encouraging each artist to bring his or her own individual style and creative originality into children's books" (Vlasov; Schwartz; Kovtun, quoted in Rosenfeld 2003, 212–13; 246–47).

More ...

For more information on Marshak and Lebedev, read these essays: "The Soviet Production Book" and "The Five-Year Plan & the End of the Avant-Garde Picture Book".

View examples of Lebedev's works in the Harer Collection »

View examples of Marshak’s works in the Harer Collection »

View examples of books created by Marshak and Lebedev as a team »