|

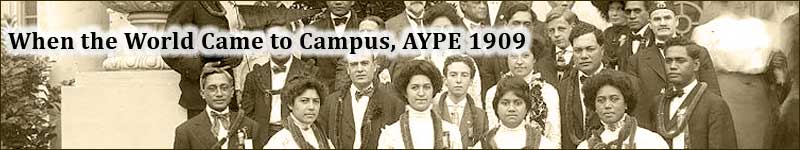

Alaska / Hawaii / PhilippinesIn 1909, Alaska and Hawaii, although they would not become states until nearly fifty years later, were already under American sovereignty. Alaska's purchase from Russia was negotiated by Secretary of State William H. Seward in 1867 and Hawaii was annexed in 1898. For the AYP, the U.S. Department of the Interior prepared exhibits that sought to educate fairgoers about the history of these regions as well as to show the bountiful resources that these territories offered for development. Although Alaska had been under U.S. control for over forty years, few Americans were familiar with this vast and distant territory. In order to educate the populace, the Government planned exhibits in the Alaska building that covered seven major areas: Mines and minerals; Fish and fisheries; Furs, animals and birds; Agriculture, horticulture and forestry; Transportation; Ethnology; and Education, women's work, and art. According to the Government's final report, the gathering of the exhibits was subject to unique logistical challenges due to the fact that once the plan for the displays was set, “only 10 months remained before the opening of the exposition, and that time included the winter months during which the greater part of Alaska is wholly inaccessible from the States.” Despite the difficulties involved, the displays that were assembled certainly hit their mark; the exhibits were extremely popular, especially those focusing on Alaska's mineral resources. One part of the exhibit, called the Gold Pavilion, housed 1 ¼ million dollars (the 1909 valuation!) worth of gold in a glass case in a specially guarded iron cage that would sink nightly into a steel vault below. Also impressive was a panorama showing a composite Alaskan landscape featuring mines, railroads, fields, and villages, and complete with lighting effects designed to simulate the passing of day and night. Overall, the exhibits were intended to ensure that, as the Government report stated, “none who saw it could fail to realize that the jeers at ‘Seward's ice box’ were without foundation.” Hawaii was also unfamiliar to the average American in 1909, and again the aim of the exhibits in the Hawaii Building was to introduce the Islands, their people, and their resources to fairgoers. To this end, a relief map of the islands set in a 50-foot tank of “real water” greeted visitors directly inside the main entrance. The U.S. appropriation for the Hawaii exhibit was supplemented by funds from the Pineapple Growers’ Association who had a significant presence in the Hawaii building, serving pineapple at koa wood tables for the “nominal” charge of ten cents a plate, near a 15-foot pineapple constructed from fresh fruit topped with palm leaves. Other tropical fruits such as bananas, mangos and avocados were also displayed, and coffee, though more familiar to American audiences, was also served. A model in brown sugar of the palace of Hawaii's pre-annexation royalty was among the exhibits provided by the “sugar interests.” Hawaiian hardwoods were prominently displayed, both polished and unpolished, and in the form of finished furniture. One of the most memorable features of the Hawaiian exhibit, though, was the music. Led by prominent Hawaiian musician Ernest Kaai, a group of singers and instrumentalists performed “almost constantly,” becoming one of the most popular attractions at the Exposition. “The amiability of the singers in courteously acceding to… frequent requests” for performances of “ ‘Aloha Oe,’ the Hawaiian dirge” was gratefully recorded by the officials in charge. The impression this music made on fairgoers is captured in a note on the back of a photograph held in Special Collections: “The Cascades colored lights behind the water falls on Honolulu Day (Hawaii)…Canoes & Row boats moved about in the pool singing Hawaiian Songs. The Moon light's song & crowd made a delightful evening.” Interestingly, local music historian Peter Blecha has found indications that one musician, steel guitar master Joseph Kekuku, remained in Seattle after the AYP was over, giving music lessons and influencing local guitar makers well in advance of the Hawaiian music craze that is generally credited as beginning with San Francisco's 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition. Although the Igorotte Village on the Pay Streak created much more of a sensation, the Philippines did have an official presence at the AYP. Briefly autonomous as the First Republic of the Philippines after liberation from Spain, the Philippine Islands came under U.S. control in 1901 after the Philippine-American War. The Philippine exhibit was prepared by the War Department and, as was stated in the official report on U.S. participation at the AYP, “indicated the progress made…in the ten years of American occupation,” and “suggested the future prosperity of the Philippine people is to be limited only by the great productive capacity of the islands.” Ethnographic exhibits featured life-size figures of the Negrito and Igorot peoples with reproductions of their dwellings and domestic activities. Cases of metal work, pottery, basketry, and cloth represented the Tagalog and Visayan groups. Colored transparencies arrayed around the main hall conveyed “a vivid description of the Filipinos and their activities,” and “the beauty of Philippine forests and rivers…” One newspaper article discussed a bowl on display, presenting it as “a good example of Filipino workmanship” and, by implication, a “good example of the progress made by the Filipinos in the arts and crafts.” Other exhibits featured the natural resources of the Philippines such as furniture and wainscoting made from native woods; gold nuggets, iron ore, copper ore and coal samples; and an extensive collection of items inlaid with mother-of-pearl including, strikingly, “a box with ten trays, all inlaid with mother-of-pearl, each tray containing 50 poker chips all of mother-of-pearl and in different colors—white, blue, red, and orange.” Items from other institutions: |