Essay: 19th Century American Theater

The latter half of the 19th century was a time of great change for the American theater. It was a time of tremendous growth in population in America, especially in cities on the East Coast. Americans had more leisure time and better standards of living, and they looked to the theater to provide entertainment -- laughter, glitter, and sentimentality. The expanding transportation system in the United States allowed actors and actresses to tour the country, bringing professional theater to many towns and cities that had never before experienced it. As the population of the country grew rapidly, the number of theaters in large and mid-size cities grew as well. From the 1850s until the turn of the century, thousands of new theaters were built.

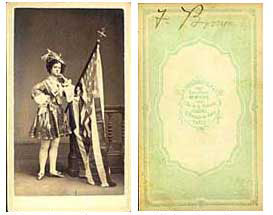

The 1828 election of Andrew Jackson as President of the United States fueled the spirit of nationalism that had been growing in the country. Hallmarks of the nationalistic movement were patriotism, optimism, and idealism, and these values were reflected in the American theater. Romanticism, the dominant aesthetic mode in writing and the arts in Europe, was embraced in America theater as well but was blended with nationalistic overtones, producing more democratic and populist themes.

Another aspect of the prosperity of this era was the growth of businesses serving the theater industry. Especially in New York City, there was tremendous growth of businesses such as dramatic agencies, costume shops, theater suppliers, photography studios, trade newspapers, boarding houses and hotels, and restaurants catering to the theater trade.

Theaters of the 19th Century

Theater design and technology changed as well around the mid-19th century. Candlelit stages were replaced with gaslight and limelight. Limelight consisted of a block of lime heated to incandescence by means of an oxyhydrogen flame torch. The light could then be focused with mirrors and produced a quite powerful light. Theater interiors began improving in the 1850s, with ornate decoration and stall seating replacing the pit. In 1869, Laura Keen opened the remodeled Chestnut Street Theater in Philadelphia, and newspaper accounts describe the comfortable seats, convenient boxes, lovely decorations and hangings, excellent visibility, good ventilation, and baskets of flowers and hanging plants.

Theater crowds in the first half of the 19th century had gained a reputation as unruly, loud and uncouth. The improvements made to theaters in the last half of the 19th century encouraged middle- and upper class patrons to attend plays, and crowds became quieter, more genteel, and less prone to cause disruptions of the performance.

Plays and Other Entertainments in the 19th Century Theater

Well into the mid-19th century, American theaters continued to be strongly influenced by London theater. Many actors and actresses of this period were born and got their professional start in England. Plays performed tended to follow the English classical tradition, with Shakespeare's plays and other standard English plays remaining popular. However, American-born playwrights and actors began to have an influence, and contemporary plays began to be performed regularly as well.

Prior to the 1850s, a theater bill might include five or six hours of various entertainments, such as farces, a mainpiece, an afterpiece, musical entertainment, and ballet. Music was an important component of early American theater, and plays were often adapted to included musical numbers. In the 1850s, the number of entertainments on a theater bill began to be reduced, first to two or three and, later, to one main feature only.

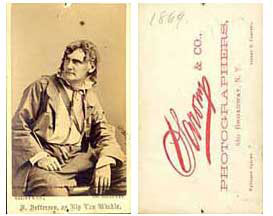

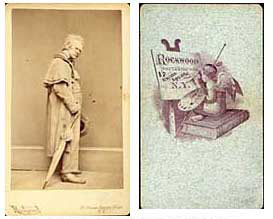

Acting styles in the early 19th century were prone to exaggerated movement, gestures, grandiose effects, spectacular drama, physical comedy and gags and outlandish costumes. However, from the mid-19th century, a more naturalistic acting style came into vogue, and actors were expected to present a more coherent expression of character. Subject matter of new plays was more often drawn from contemporary social life, such as marriage and domestic issues and issues of social class and social problems.

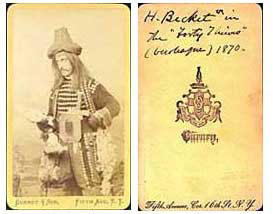

Another favorite form in 19th-century theater was the burlesque (also called travesty). The plays of Shakespeare, especially those in the regular repertory of the legitimate theaters, were a favorite target. Many actors were known primarily for their comedic and burlesque acting talents.

Structure of Theater Companies

Along with plays and actors, America inherited the "star system" from Great Britain. Stock theater companies were established in large cities on the East Coast and in New Orleans. The cast was then supplemented by visiting theatrical stars, who toured the country for just such purpose. Stock companies were self-sufficient and mounted productions on their own when no star was visiting, but by the 1840s, so many stars were touring the United States that most companies were rarely without the services of at least one big-name actor or actress.

Stock companies usually had an actor-manager who was responsible for all details of business and production. Managers of these companies were quite powerful and their word was law in the company. The manager often made significant changes to a playwright's work, and the playwrights had no recourse to prevent this until the passing of the Dramatic copyright Act of 1833. Even then, the Copyright Act only covered printed plays.

Theatrical productions were rotated regularly, often daily. However, long runs of 100 or more continuous performances were not unusual and became common in the latter decades of the 19th century.

In the last half of the 19th century, the star system gradually gave way to the "combination system." Managers found that, rather than hiring a continuous stream of high-priced stars, it was more economical to take the entire theater company on the road to tour. Companies would spend the summer in their home city, usually New York, Boston, or Philadelphia, and then would be on tour again beginning in October. A "season" usually consisted of 39 weeks.

American Theater and the Civil War

The American theater was only moderately affected by the outbreak of the Civil War. Some theaters closed down in the first year of the war but then reopened, even in the South. However, touring was severely limited in the northern states and stopped all together in southern states. A few leading actors volunteered for service but the majority continued to pursue their profession. One of the biggest theatrical events during the Civil War was the popularity of the play UNCLE TOM'S CABIN. At one point, four shows were thriving in New York City at the same time. After the war, many southern theaters never regained their stature, even as the theater industry in the north and west grew rapidly.

Theater Life

In the 18th century and early 19th century, the acting profession was considered sinful and actors were subject to social ostracism. However, by the mid-19th century actors could be considered quite socially respectable. "Prominent persons in society, politics, and literature went out of their way to entertain leading members of the acting profession, while lesser actors seemed to have no trouble fitting into middle-class America. The memoirs of theatrical people like Wood, Ludlow, Smith, or William Warren gave no suggestion of social ostracism. On the contrary, once established in their profession, they became solid and respected citizens. Of course, to some extend their background, to a greater degree their modest salaries, limited actors' social success. But if actors succeeded, lived decently, and, perhaps most important, made money, they were socially accepted." (Grimsted)

The life of actors and actresses in the mid-19th century was very hard, requiring great physical stamina. In addition to a grueling performance schedule, actors must withstand stagecoach and early riverboat travel in addition to makeshift lodgings. Actors would often rehearse as many as three plays during a day and then would have to prepare for the night's performance. By the Civil War, the season was varied and demanding. A season could consist of 40 to 130 plays, changing nightly. Utility actors in a company might be expected to know over 100 parts. The famous actress Charlotte Cushman would offer 200 different lead roles. Actors were usually expected to learn a new part within two days, sometimes overnight.

In the antebellum period, beginning actors' salaries ranged from $3 to $6 per week; utility players' salaries from $7 to $15 per week; "walking" ladies and gentlemen, $15 to $30; and lead actors were paid anywhere from $35 to $100 per week. Traveling stars could command $150 to $500 per 7- to 10-day engagement, plus one or more benefits. Except for the lowest ranks of actors, these salaries were good for this period, especially for women, even though they were paid less than men in comparable roles. Actors and actresses were expected to furnish their own costumes.

Many of the actors and actresses of the 19th century came from theatrical families and backgrounds, and many got their start in the theater as children. "Child stars are an American tradition...but no period surpasses the mid-1800s for the sheer number of children appearing in live theatrical events or the degree of seriousness with which they were taken. And, unlike their modern counterparts, they more often than not drew recognition by play adult roles." (Hanners) However, these children usually played scenes from plays, such as those of Shakespeare, rather than playing the role in a complete production.

"Because the theatre has been remarkably free-thinking, women in the profession have always been relatively equal to their male colleagues. Bad managers have absconded with their salaries equally; audiences booed them equally; they starved equally between engagements; and their contributions to the traditions of the theatre have been equally forgotten."(Turner) Especially in the 19th century, women's roles in theater were rather ambiguous. The traditions of the time required women to be delicate, fragile, and dependent. However, the rigors of the acting profession necessitated that they be resilient, independent, strong-willed and determined.

Among the many problems faced by women in the theater, one more lighthearted problem was that of dealing with fashions of the day. Clara Morris recounted that long trains on dresses were particularly vexing. She tells the story of Fanny Davenport having to move about quite a bit on a crowded stage during a comedy scene, ending up with her trailing skirts so thoroughly wrapped around a chair that upon exiting the stage, the chair went right along with her.

The Photographers

Several photographers and photography studios achieved a certain status of their own in the theater industry. Among the most famous was Napoleon Sarony. Sarony established a studio on Broadway in 1866 and, for the next 30 years, photographed virtually every actor and actress working on the New York stage. Other famous photographers and studios of this era were Charles D. Fredricks & Co. and Jeremiah Gurney of New York; Washington Lafayette Germon of Philadelphia; and Matthew Brady, who associated with the E. & H.T. Anthony Studio of New York.

Cartes-de-visite were small visiting card portraits, usually measuring 4½" x 2½". A Parisian photographer, Andre Disdéri, introduced them in late 1854. He patented a way of taking a number of photographs on one plate, thus greatly reducing production costs. Different types of cameras were devised. Some had a mechanism that rotated the photographic plate; others had multiple lenses that could be uncovered singly or all together.

The carte-de-visite did not catch on until one day in May 1859 Napoleon III, on his way to Italy with his army, halted his troops and went into Disdéri's studio in Paris, to have his photograph taken. From this welcome publicity Disdéri's fame began, and two years later he was said to be earning nearly £50,000 a year from one studio alone. During the 1860s the craze for these cards became immense.