Historical Background of the Former Yugoslavia

Until WWI, Austria-Hungary ruled the territories of today’s Slovenia, Croatia, Vojvodina, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the Ottoman Empire controlled Serbia and Montenegro until 1878, and Macedonia until 1912. “People identified mostly with their historic regions or lands until the nineteenth century, when the development of capitalism and integration processes caused the birth of modern national identities—so that Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Bosnian Muslims (present-day Bosniaks), Macedonians, and Montenegrins each started to identify themselves as ethnic nations.” Also at this time, there was a resurgence of interest in regional dress, which coincided with a romanticized and idealized idea of the peasant past, which solidified in the idea of “our dress,” emblematic of national identity.

In 1918, Serbia and Montenegro united with the South Slavic territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, which resulted in the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. In 1929, this entity became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was occupied by Axis forces and became the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, and in 1945, the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. This entity was renamed the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963. In 1991, it disintegrated into five independent states: the Republic of Slovenia, the Republic of Croatia, the State of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (including Serbia and Montenegro), and the Republic of Macedonia. Currently, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia are all independent states. Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia in 2008, with oversight given to the United Nations. From 1929-1941, the territories of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia were known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, a monarchy ruled by King Aleksandar Karadjordevic. The unification of the South Slavic peoples was considered the “Yugoslav idea”:

The “memories” and glory of their ancient states represent not only the mythical foundations of these (ethnic) nations but also historical foundations of their present nation-states. Although specific circumstances and historical developments of different parts of this territory included foreign rule by different hegemonic empires—resulting in specific ethnic identities and formation of distinct modern ethnic nations—strangely enough, the myths and memories of common ethnic origins and ethnic kindred survived and found their reflection in the emergence of the “Yugoslav idea” in the nineteenth century…

Despite this desire for unification, tensions between various ethnic groups remained and were agitated when the Kingdom of Yugoslavia refused to acknowledge ethnic and political pluralism and recognize rights of ethnic minorities as it had promised to in several agreements. However, despite constantly shifting political boundaries, folk culture of the time reflected individual ethnic identities, especially through distinctive regional costume. After the dissolution of Yugoslavia into independent countries, there was a renewed interest in cultural heritage, especially in regional costume and activities like traditional dance and festivals.

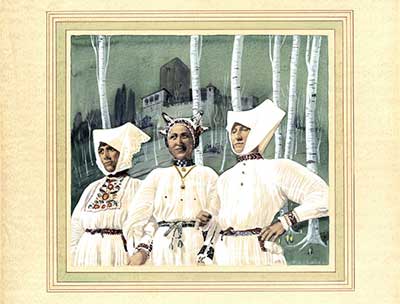

Regional Costume in the Former Yugoslavia

During the time of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929-1941), Yugoslavia was composed of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, which included Kosovo and Macedonia (then known as Southern Serbia), and Slovenia. The countries that made up the former Yugoslavia are in turn made up of myriad peoples who have also been historically influenced by each other and larger bordering powers, such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy, and Eastern lands. The people were South Slavic and spoke Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, or Macedonian. There were two alphabets, Roman and Cyrillic. There were three major religions: Roman Catholicism, the Serbian or Macedonian Orthodox Church, and Islam. In addition, there were non-Slavic populations that lived there, including Albanians, Hungarians, Romanians, and Turkish peoples.

Although women formerly hand-made clothing which was altered and worn throughout one’s lifetime, regional costume was mostly worn only for festivals and traditional dance by the time of WWII. Various factors influence regional costume, including social station, marriage status, age, and season, as well as interaction with other countries and the impact of new technologies resulting from industrialization. In the formerly feudalistic society, sumptuary laws were imposed that limited designs of costume, but once they were lifted, rural clothing grew more elaborate and distinctive based on geographical isolation. Each village had very distinctive customs and costume, regardless of political boundaries.

However, regional costume from the former Yugoslavia shared several common features. Costume was generally made of linen or wool, originally hand woven, but was later replaced by store-bought cloth. Due to changes in technology, new (non-traditional) kinds of materials and dyes became available. Traditional crafts such as tailoring declined; therefore, types of embroidery (such as with gold thread in Bosnia and Herzegovina) became less common. As embroidery became more commercial rather than something that was done in the home, new fashionable motifs were introduced to please urban buyers, rather than village people. Costume ranged in color from monochromatic to very colorful, and embellishment from very plain to sporting leather and cloth appliqué, decoration with metallic thread, and heavy embroidery.

A woman’s costume consisted of an ankle length shirt, skirt and blouse combination (of varying lengths), or a dress, depending on the geographical region. In some regions, women wore long baggy trousers. Over the undergarments women would wear one or two aprons, then an overcoat, varying in style from short to long, sleeveless to long-sleeved. Accessories included a belt or sash of some kind, leggings or stockings, and soft leather shoes. Layers would be added and removed to reflect the climate conditions of a particular season.

Headdresses also ranged from small caps and folded kerchiefs, to elaborately wrapped head coverings, or ribbons. Hairstyles varied according to location of the village, by marital status, or age, and women would often weave flowers or coins into their hair as a sign of womanhood. Many times, women carried embroidered bags and wore necklaces made of coins or clothing decorated with coins. This sort of clothing was often a young girl’s dowry. Women’s costume generally varied in color, which sometimes indicated marital status.

A man’s costume generally consisted of cotton or woolen trousers, which could be fitted or loose, belts or sashes, leggings and stockings worn with soft leather shoes, work shoes, or boots for special occasions (in some regions). Various types of head coverings were worn, including caps and fezzes. Over the clothing, men would wear various layers of waistcoats, long coats, and hooded or sheepskin coats, which would often be heavily embroidered or adorned with metal thread. For special occasions, many men would wear belts with pouches to hold their smoking implements and weapons. Costume and linens for household use were decorated with appliqué or embroidered motifs. These patterns were usually geometric, but often display Turkish-influenced floral motifs. Geometric symbols included triangles, zigzags, rhomboids, labyrinths, crescents, circles, stars, and crosses, as well as stylized motifs from the animal world. Certain colors were often used in embroidery, such as bright red, white, violet, and silver and gold thread.