From the moment of Napoleon's coup d'état, he crystallized the hopes of both the royalists and the republicans. The royalists saw him as offering an assurance that the Bourbon monarchy would be restored. However, Napoleon quickly made it clear that was not his intention. At the same time, he distanced himself from his republican supporters in order to impose his own concept of power. He quickly moved to put a large number of newspapers out of publication, and censored those that were left—thus eliminating a key source of communication. Both constituencies eventually turned on him, using pictorial art as a means of expressing their opposition. Distribution of the prints was extremely dangerous and therefore limited until the waning of Napoleon's power following the disastrous Russian Campaign.

French cartoonists were well-educated, talented, and loyal to the ancient regime. The French captions are well-written, annotated with beautiful calligraphy, and full of allusions to classical mythology and historical events, literary quotations, and parodies of well-known painters. Some of the artists were known during their lifetimes, but many worked anonymously due to the great danger of publicly criticizing the Empire. Most publishers, too, distributed the prints clandestinely—no shop window showings occurred in France, or at least until after Napoleon's fall. At the first hint of an anti-Napoleon print in circulation, Napoleon sent his secret police to root it out.

Unlike English prints, the French prints do not caricaturize Napoleon's body. Instead, they focus on Napoleon's failures and on his threat to the stability and future of the country. Many royalist cartoonists concern themselves with the legitimacy of his power and his fitness to govern. These artists addressed two separate audiences, with a different political message for each one: for the royalists, hope for a return of the Bourbon royal family; for the bourgeoisie, fear of renewed republican chaos and terror. You can see these messages and the strategies used to convey them in a few examples:

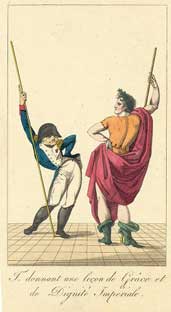

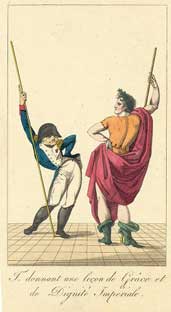

T. donnant une leçon de Grace et de Dignité Impériale

|

The cartoonists wanted to destroy the sacred aura that Napoleon and his propaganda machine worked so hard to establish. Official art put forward a timeless image in the style of classical heroes, sometimes going so far as to portray Napoleon in Caesar-like costume. Some of the prints, like this one, ridicule that image. Talma, the figure shown with Napoleon, was an actor known for his success in Greek theater; the artist suggests that Napoleon needs lessons in how to act like an emperor.

Le Déserteur

|

Since Napoleon drew much of his reputation from his military prowess, many cartoons from the last few years of his reign attacked that reputation, depicting him as a coward. During the debacle of Waterloo, Napoleon fled the battle field, ostensibly to return to Paris to organize its defense. This was a disastrous move. Afterwards, the Royalists wanted to make sure he was discredited for his, and used caricatures such as this to stress his flight from the battle and his propensity to have others sacrifice themselves for him.

Ah mon dieu papa comme tu es rempli de poux

|

They also wanted to separate him from his base of support among the revolutionaries. This wasn't hard to do, since the Jacobins were suspicious of him from the time he proclaimed himself Emperor. In this print, he flicks fleas off his coat, dismissing his son's concerns by saying the vermin are only the fédéres (revolutionary ruffians who had staged a huge rally on Bastille Day 1790.)

Et l'on revient toujours A ses premiers amours

|

The royalist artists also continued to remind the bourgeoisie of Napoleon's link to the revolutionaries, using prints such as this one that proclaims that “one always returns to one's first love”. The bourgeoisie was terrified that a change in regime would lead to a replay of the chaos of the Terror, and the artists played on this fear to pave the way for the return of the monarchy.

Finally, they tried to show that the promises of “peace and prosperity” under the Empire were unattainable, and that Napoleon's continuing reign was causing great harm to France, her people, and her economy.

Le Carnaval de 1815

|

In “Le Carnaval de 1815” , Napoleon was again shown as Harlequin, and his chief aide Cambacérès as Pulcinella (both comic figures from the Commedia dell'Arte.) The strands of macaroni represent the many conscriptions that were necessary to replenish Napoleon's armies, and the bags of money show the resources that continued to be expended on the constant state of war.

La France Constitutionnelle

|

In “La France Constitutionelle” the artist shows a gravely wounded France, being ridden by a victorious Napoleon. Papers spilling out of the cornucopia at her feet are labeled “forced loan, levy of 400 million…”