World and Regional Maps Collection, 16th to 19th Centuries

Exploration and Discovery

The historic period commonly known as the European "Age of Exploration" from the 15th century to the 18th century was a series of attempts to explore, map and verify knowledge of the world. Spanish, English, Dutch and Russian explorers were part of this interest, returning to Europe with accounts that would revise and enhance conceptions of world geography. Evidence of their exploration and discovery are often depicted throughout rare maps as "tracks" sometimes accompanied by illustrations of miniature sailing vessels. In addition, cartographers often supplemented their maps with short descriptions or comments on exploration to offer clarity on newly discovered regions. Maps in this collection of particular interest are the routes of the explorers Magellan, Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, James Cook, Vitus Bering, Aleksei Chirikov and others who navigated the North and South Pacific Oceans.

Cartographic Curiosa

Maps with major geographical inaccuracies are referred to as "Cartographic Curiosa." These maps often display misshapen continents, incorrect river sources, and islands as peninsulas and vice versa. These distorted depictions were often based on explorers’ erroneous reports or previous maps’ errors. Examples of such geographic mistakes include New Guinea joined to northern Australia, Japan’s landmass being overly exaggerated when compared to the rest of Asia, and California displayed as an island. Mapmakers were sometimes slow to adjust to revisions based on continued exploration. For instance, one cartographer refused to depict California as anything but an island, even after verified accounts of its status as a peninsula had spread throughout Europe.

Northwest Passage

Driven by an attempt to find trade routes to Asia, European powers sent explorers to seek a Northwest Passage through the Arctic regions connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first recorded attempt to discover the Northwest Passage was the east-west voyage of the Italian explorer John Cabot in 1497. For the next four centuries, explorers continued to search for this mythical route despite repeated failures. Contemporary maps did not facilitate the situation as many frequently depicted imaginary passages. As early as the sixteenth century, Abraham Ortelius’s world map, "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum," depicted a Northwest Passage via the Strait of Anian. Two hundred years later the English, Spanish and Russians were still occupied with trying to find this route. Many maps in this collection that depict the northwest region of North America show the traces of explorers who traveled as far north as they could before being thwarted by Polar ice. It was not until 1903 that a passage was successfully navigated through the ice by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen.

California as an Island

The concept of California as an island emerged roughly during the early 17th century. Earlier maps had depicted California correctly as a peninsula. The erroneous "island" notion has been attributed to the Carmelite Friar, Father Antonio Ascenscion, who probably formed the idea based on a "misconception" of the exploration accounts of Juan de la Fuca in 1592 and Martin d’Aguilar in 1602. One of these explorers reported a large opening along the west coast of North America and the other mentioned a large "inland sea" north of Cape Medocin. In 1620, Father Ascension sent a map depicting California as an island to Spain by ship. This ship was captured by the Dutch resulting in the map being sent to Amsterdam. In 1622, Michiel Colijn of Amsterdam printed a title page vignette that showed California separated from the mainland. The idea was perpetuated by English cartographers when Henry Briggs published the first English map to show California as an Island in "A Treatise on the North-West Passage to the South Sea" in 1625. Both of these men purportedly modeled Ascenscion’s map. However, many Dutch cartographers ignored the "California as an island" concept and followed the work of their sixteenth-century predecessors whose maps had depicted California as a peninsula. Of note, the prominent Dutch mapmaker Nicolaes Visscher promoted the idea as did Jan Jannson in a 1638 map. California was appropriately identified as a peninsula in the late 17th century. In 1705 Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, a Jesuit missionary, created a map of the Baja Peninsula after leading an overland expedition there from Arizona. Although some cartographers resisted Kino’s idea, such as Herman Moll who argued that trusted contemporary explorers had indeed sailed around California, subsequent exploration in Baja California confirmed the peninsula theory. Despite this, California was still depicted as an island well into the middle of the 18th century even though in 1747, Ferdinand VI of Spain issued a royal edict declaring California as part of the mainland (Tooley, 110-11).

Source:

Tooley, Ronald Vere. "Chapter 3: California as an Island: A Geographic Misconception Illustrated by 100 Examples from 1625 to 1770." In "The Mapping of America." Ed. by Ronald Vere Tooley. London: Holland Press, 1985. 110-134.

Pacific Northwest

The mapping of the region known today as the "Pacific Northwest" is a story of difficult land and sea voyages and apocryphal accounts involving Spanish, Russian, English and American explorers. The Treaty of Tordeillas in 1493 gave Spain the first opportunity to explore North America and for the next three centuries Spanish explorers pursued their quest for wealth up the west coast. As part of the persistent search for a Northwest Passage for use as a trade route around the northwestern part of North America, explorers from other European nations were dispatched north up the North American western coastline for hundreds of years beginning in the 15th century. In 1564, the Flemish cartographer and geographer Abraham Ortelius created a world map, "Orbis Terrarum," that was one of the first that noted the existence of a Northwest Passage via a mythical Strait of Anian. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake explored the coast of Oregon and named the new area "New Albion," claiming it for Queen Elizabeth I. In 1592, Juan de Fuca, a Greek navigator in the service of the Spanish King Philip II, claimed to have found the Strait of Anian at 49 degrees north. The Spanish admiral Bartholomew de Fonte supposedly sailed along a waterway that stretched from east to west along northern North America in 1640. It was not until the end of the 18th century when information from Russian exploration in the 1740s, Captain James Cook in 1778-1779, and further surveys conducted by George Vancouver in 1793 helped shape the geography of the Pacific Northwest coastline. By the early 19th century the transcontinental explorations of Lewis and Clark west to the Columbia River had led to a more accurate mapping of the interior. Maps in this collection up until the early 18th century show how little was still known regarding the geography of the region, revealing many myths about the area such as the Sea of the West, the kingdom of Quivira, and the River of the West. Maps from the end of the 18th century onward show much greater accuracy. Also included in this collection are 19th century maps depicting major cities of the Pacific Northwest, including Seattle, Tacoma and Victoria.

Source:

Inglis, Robin. "Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Northwest Coast of America." Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2008.

Alaska

Alaska was first mapped by Russian explorers in the 18th century when Peter the Great sent out the Danish navigator Captain Vitus Bering to lead an expedition to determine whether Russia and America were connected by a land bridge or separated by sea. Although he eventually established the continents as separate land masses, Bering’s first expedition (1724-1730) failed to establish the presence of the Alaska coastline due to fog. In 1732, Russian explorer Mikhail Gvozdev sighted the eastern coast of the Diomede Islands in what is now the Bering Strait, prompting further exploration. During the Second Kamchatka Expedition (1741) Bering was able to explore the Aleutian Islands and determine a general outline of Alaska’s southern coast. Unfortunately, on his return to Kamchatka, Bering was shipwrecked on modern-day Bering Island and died.

In 1762, Catherine the Great sent Lieutenant Ivan Synd out to survey the Alaskan peninsula. He was able to provide a map, albeit inaccurate, of the Aleutian Islands chain. Although further explorations of the Aleutian Islands and western regions of the Alaska Peninsula were made by Captain Petr Krenitsyn and Lieutenant Mikhail Levashev in 1768, it was not before the 1770s that a map of the entire Aleutian chain was finally completed by the Russian navigator Potap Zaikov. By the 1790s, Russia had laid claim to most of coastal Alaska and had monopolized the fur trade through the establishment of the Russian American Company in 1799.

Other explorers surveyed parts of Alaska in their attempts to locate a Northwest Passage. In 1792 the British explorer George Vancouver reached latitude 50 degrees, 20’ north and explored an area near Juneau that he named Port Conclusion (Hayes, 102-5).

Subsequent explorations and mapping took place after the purchase of Alaska by the United States in 1867, primarily under the leadership of the U.S. Coastal Survey and the U.S. Geological Survey. The northern reaches of Alaska were ultimately defined by the polar explorations in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Source:

Hayes, Derek. "America Discovered: A Historical Atlas of North American Exploration. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2004.

Mythical Places

Early maps often refer to mythical or legendary places. Charts of geographic regions unknown to Europe prior to the 1400 or 1500s often contained apocryphal and sometimes exaggerated or unsubstantiated explorers’ accounts. These places were frequently perpetuated as reality through the system of copying, re-engraving and reprinting that was common among cartographers and publishers. For example, accounts of the legendary "Sea of the West" in the Pacific Northwest region of North America are depicted on many maps well into the late 18th century. Other mythical geographic features common to the maps in this particular collection include the kingdom of Anian in northwest modern-day United States, the isle of Iesso north of Japan, Lake Chiang Mai in China (sometimes shown as the source of major rivers), and various depictions of two lakes as the source of the Nile River in Africa.

Quivira

Mythical kingdoms often appear in maps of unexplored regions of the New World. These inaccuracies were often due to faulty reports from early explorers and a relentless quest for fame and fortune, whether it was for gold or the Northwest Passage. The land of Quivira was no exception. In 1543, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, the governor of New Galicia in New Spain (now known as Mexico), led an expedition northward to search for gold. During the expedition, Coronado sent out smaller parties for further exploration. One party led by Hernando de Alvarado headed northeast towards the Great Plains and returned with a Native American who spoke of a "city of gold" he called Quivira (an area near modern-day Kansas City). Coronado responded favorably to this report and immediately headed northeast to discover Quivira for himself. Describing Quivira, he wrote that it had "land as level as the sea" and many buffalo though it lacked gold (Hayes, 22-3). In 1569, the cartographer Mercator drew a map relocating Quivira further west to the coast of North America instead of the Great Plains as did Abraham Ortelius in his map entitled "Americae sive Novi Orbis" published in 1570. In subsequent maps created as late as the 1700s, the land of Quivira persistently appears in the northwestern region of the modern-day United States (Hayes, 23).

Sources:

Hayes, Derek. "America Discovered: A Historical Atlas of North American Exploration. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2004.

Anian

Anian was a mythical kingdom that appeared on many maps of North America, particularly in the northwest region of modern-day United States and further to the north near the Bering Strait. The name originates from Marco Polo’s accounts of travels in Asia in the 13th century. The kingdom first appeared on maps of east Asia in the 15th century, but in the 16th and 17th centuries was relocated to North America (Wagner, 426). The Strait of Anian was first recorded in a pamphlet in 1562 by Giacomo Gastaldi and then on a map in 1566. Subsequent maps usually showed the narrow strait at 67 degrees north latitude, "connecting the Pacific Ocean with the Polar Ocean" (Wagner, 426). Other cartographers located the Strait of Anian near Japan where it supposedly was mislabeled by the Dutch explorer De Vries in 1643 (Wagner 426). Anian and the associated Strait of Anian eventually became known as the Bering Strait in the 18th century (Hayes 34).

Sources:

Hayes, Derek. "America Discovered: A Historical Atlas of North American Exploration. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2004.

Wagner, Henry R. "The Cartography of the Northwest Coast of America to the year 1800 Volume 2." Berkeley: University of California Press, 1937.

Historical and Allegorical Illustrated Scenes

Many maps, especially those from the 17th century, incorporated illustrated scenes that figured prominently in the decoration of the cartouche or were presented as separate decorative elements. Sometimes these decorations made reference to persons with political prestige who commissioned and supported the cartographers. For the most part, however, they described specific historic events, often depicting figures clothed in indigenous dress common to the geographic area shown. In addition, these scenes were often filled with symbolic objects: chests of gold and agricultural produce representing wealth; cartographic instruments for exploration; and animals for the exotic. On occasion, labeled keys provided map readers with useful information about the illustrations. Rare maps also often depicted allegorical scenes with classical, religious, or mythological figures. Common tropes included illustrations of the god of the sea Neptune, symbolizing dominion over the sea, and the female figure of justice. Within this collection, many maps of the Americas depict vignettes of Native Americans and their first encounters with Europeans or missionaries. Often such images represented Native Americans as royalty, perhaps suggesting the notion of the untainted "noble savage." (Potter, 26).

Source:

Potter, Jonathan. "Collecting Antique Maps: An Introduction to the History of Cartography." London: Jonathon Potter Ltd, 1988.

Bird's Eye View

Bird’s eye view projections show maps with an "oblique" view of a town or city. From this perspective, a town’s layout is visible as are buildings, "streets, parks, and blocks" (40). This type of projection was quite popular in the United States during the late nineteenth century. Often, these viewpoints show cities in great detail and show surrounding geography as well. Most of this collection’s bird’s eye view maps are of cities in the Pacific No

rthwest, including Seattle, Tacoma and Victoria, though a select few illustrate European cities.Source:

Manasek, F. J. "Collecting Old Maps." Norwich, VT: Terra Nova Press, 1998.

Polar Projection

A polar projection shows one of the earth’s pole at the map’s center. Such maps usually present the world "as though viewed from a great distance" (Manasek, 36). A small number of world maps in this collection include polar projections of the world viewed from the North and South Poles as inset maps. Of note, "Polus Antarcticus" by Hendrik Hondius shows the world from the South Pole, offering an interesting perspective on the geographical conception of Australia at the time.

Source:

Manasek, F. J. "Collecting Old Maps." Norwich, VT: Terra Nova Press, 1998.

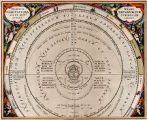

Celestial Map

Celestial maps depict constellations of stars as they appeared at certain geographical locations during different seasons. They usually contain an illustrated diagram overlaid on top of the stars in order to show which constellations appeared in the night sky. A small number of celestial maps or inset celestial maps appear in this collection. The most intriguing of the group is "Globi Coelestis In Tabulas Planas Redacti Pars III," showing detailed illustrations of the major astrological figures on top of the star map.