Essay: Marbled Papers

The origins of marbling are often disputed, with its early development claimed by several countries: China, Japan and the countries of the Middle East. Albert Haemmerle suggests that art forms resembling marbling were seen in China as early as the Ming Dynasty (14th-17th Century). Chinese professor Tsuen-hsuin Tsien, who has studied the subject extensively, also believes that the earliest style of marbling originates from the Chinese. But another form of marbling, preceding the Chinese, is Suminagashi, a style attributed to the Japanese as early as the 10th century. Centuries later, marbling of a related nature, emerged as an art form in Turkey (known as Ebrû) and in Persian countries (known as Abri) in the 15th century. Travelers to these areas of the world took note of this art form and began importing marbled paper into Europe sometime around 1600. Europeans then tried to reproduce these amazing designs. Each time the art of marbling captivated a new artist, the work would take on a new appearance, tempered by cultural identity, availability of materials and the artist's creativity.

Although papers imported into England and Europe were used for a number of decorative purposes, many of them first gained significance in highly popularized friendship albums, known as album amicorum, popularly traded among university students. As European artists cultivated the art of marbling, cultural patterns emerged prompting styles to be associated with specific countries. Modern scholars of marbling history can use these patterns, their color combinations and paper choice as a means of tracing a book's transmission through Europe.

The politics and habits of communication typical in early European systems of apprenticeship and guilds resulted in little documentation of the marbling process. Recipes for specific colors or for chemical solutions needed for certain patterns were not generally passed on from master to apprentice, causing this vital information to disappear. These practices contributed to the limited historic documentation presently available describing the process of marbling, its various patterns and recipes. It was not until the last part of the 19th century that several marblers, such as Halfer and Woolnough, published this information, including samples. The reprint publication of The mysterious marbler James Sumner in 1976 by Henry Morris of the Bird and Bull Press spearheaded a new, open and collaborative movement in the field. Since that publication, a search of OCLC on the terms “marbling” and “marbled papers” turns up over 1,500 items.

Despite the lack of authoritative marbling terminology at least eleven centuries of artists and craftspeople have devoted their passion and perseverance towards the making of these intricate, delicate but distinctive patterns.

Suminagashi

Suminagashi is a marbling technique which was exclusive to the Japanese imperial house and nobility for more than 400 years. American marbler Phoebe Jane Easton describes the process as: “…the floating of colors on a liquid to form a pattern, which may be lifted by placing a sheet of paper on the floating colors and then removing it.” (“Suminagashi: The Japanese Way with Marbled Paper,” 1972)

The creation of Suminagashi (‘sumi’ means ‘ink’; ‘nagashi’ means ‘floating’), in the traditional way, requires Sumi inks and a surfactant made from tree resin. Sumi inks are heavy in pigment but stay afloat on the surface of clean water. The artist drops Sumi ink onto a bath, then surfactant is dropped consecutively in such a way as to form rings on the surface of the water. The rings form a series of concentric lines; from here they are manipulated into wavy, moiré-like configurations by a stylus or by fanning or blowing gently at the water.

Western marbling

Traditional western style marbling (European and American), to paraphrase Richard J. Wolfe, is when the colors are manipulated into patterns or configurations by physical or chemical means and then transferred by absorption onto paper or onto book edges by bringing the paper or book into contact with the medium.

Like Suminagashi, this process is done when inks are made to float on top of a water bath. In this case the water-based colors (ink and/or paint) can only stay afloat on the surface of water heavily thickened by size. The size, in modern Western tradition, is made from a type of moss called Carrageenan.Prior to the use of Carrageenan marblers used Tragacanth to thicken their bath water. Similar to the Suminagashi process, the inks are dropped onto the surface of the bath and then manipulated with some type of implement (such as a stylus, rakes or combs).

Water-based inks float for short periods of time; during this window of opportunity the colors can be manipulated into a wide variety of patterns. Inks stay on the paper when alum is applied to the surface at the beginning of the process. An alum treated paper is then laid gently and as evenly as possible onto the surface of the bath once the desired pattern is achieved. With a few ‘happy pats’ done (a technique described by Northwest marble artist Don Guyot to hopefully lessened the possibility of air trapped between paper and bath), the finished marbled paper is lifted from the bath and laid onto a waiting board to be rinsed by clean water.

Marblers often speak of the temperamental nature of this process as it is altered by temperature, humidity, the types of paper used, quality of inks, thickness of size, shaky hands and even dust particles.

How to classify and catalog different patterns

When examining classification of marbling patterns, it is important to know that although many texts have been written on the subject, none is universally accepted as the ultimate authority. Historically patterns have been given idiosyncratic names, based on various criteria: the techniques used in their making, cultural practices or artist's whim. The result is that patterns have multiple names.

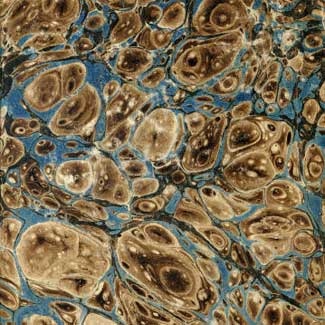

One way to group patterns, for example, is not by individual name but instead by their manipulation. Carina Greven noted in her article, The Development of a Standard Nomenclature for Marbled Paper, (Ink & Gall winter 1993) how to separate the groups, saying the first is kiezelmarmers (pebble or stone marbles), the second are the getrokken marmers (drawn marbles), the third are kammarmers (combed marbles), the fourth are the schaduwmarmers (shadow marbles), the fifth is fantasiemarmer (fantasy marbles), the sixth is combinatie-marbers (combination marbles), and the seventh is the overmarmer (over marbles). Wolfe simplifies this system into two groups, that is to say, Spot (Thrown) and Combed. (pg 183)