Excerpt: Dame Fashion

The following text is excerpted from the book Dame fashion, by Julius M. Price, London : S. Low, Marston [1913]

1800-1815

Fashions in Paris during the early years of the century changed so frequently and with such slight alterations that it is almost impossible to enumerate them, though, as compared with the Directoire period, there are many features of interest to be noted. There was a tendency towards, wearing Eastern draperies, which was probably suggested by Napoleon's Egyptian campaigns, and this is the only indication we have of any interest having been taken in Paris in connection with the mighty deeds of the, French armies. Another note of colour in costume was supplied by long scarves of bright coloured silk draped over the shoulders or hung over the arms. These scarves were frequently edged with valuable fur. About this period one, notices round the hem of the skirts a suggestion of the frills which were to assume such grotesque proportions later on. Sunshades of a peculiar shape now began to come into fashion. Jewellery was much worn: long earrings especially; and there was a craze for diamonds and topazes. The Empire, though it brought about great social changes in France, did not, at least for the first year or so of its existence, alter the fashion to any marked extent. The tendency for some time was still towards the antique and the relatively nude, but with the return of a Court, with all its imposing functions and State etiquette and festivities, women's dress gradually became more elaborate, and at length reached a point when for magnificence it has never been surpassed. The Oriental style was especially copied; richly embroidered muslins, drapery interwoven with gold and silver, or decorated with garlands of flowers, and a profusion of jewellery completed the attire of the fashionable women towards the close of the Empire period, an attire which was certainly not the least remarkable of the many changes during the evolution of fashion in the previous fourteen years.

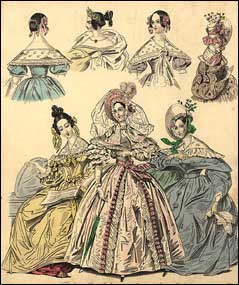

1820-1836

There now followed in England a noticeable leaning towards new and untrodden ground in the domain of fashion. No longer restrained by the trammels of the conventional semi-classical modes of previous years, London couturieres, in their endeavour to attain originality, often achieved results which were quite remarkable. Starting, as usual, with the French fashion as their models, they ended by producing effects quite startling in their incongruity. From 1820 till 1832 were years of singular ugliness; a glance at the fashion-plates of the period is sufficient proof of this to the student of costume. Nothing so peculiar in its grotesqueness had been seen for many generations, yet it was considered very attractive at the time (as all modes are whilst they are in fashion) and worthy of the best literary efforts of the fashionable journal of the day, the "Belle Assemble". How delightfully lucid for instance is the following delineation by the Editor of a "smart dress": "The corsage of redingote gowns is en blouse, but scarce visible because the pelerine being ornamented with large dents-de-loup reaches nearly to the wrist. Some of these are boullona'd with clear muslin, and with this a scarf of bareges is quite de rigueur. Capotes decline in favour, but Canezons are getting popular. We "(says the Editor)" have just seen a Canezon of white net, back full and bust ornamented, but we should observe that corsages for dress are ornamented en fichu, which is particularly becoming to belles of a slender form," for reasons which the Editor of the magazine proceeds to detail, but which it is not necessary to repeat, except that the decoration was of tulle. "Tuckers d Venfant," he continues, "are much adopted, but long ones either ornamented with bouillons or creves of a transparent material are also worn. Maltese collars or collars a la Chevaliere, either pointed d la Vandyck or bound with rouleaux, have appeared. We have seen a dress made of a beautiful material for rural parties, with long bouffant puffs, the corsage, white satin, the sleeves of tulle, the waist d I'antique with ornamented flounces of lens in demi pariere, with the old bias folds."

The hat to go with this delightfully simple dress, which by the way is given as for morning wear only, is thus described : it is composed of "Spartiere ornamented with the same material en fers de cheval". Between the interstices of this trimming are placed bouquets of full-blown roses with their buds, crowned with a plumage of flat pink Ostrich feathers. If this is not considered sufficiently elaborate the following structure is recommended-"a Parisian hat of pink gauze ornamented with detached sprigs of purple iris, and ears of green corn and long lappets of pink gauze doubled in bias and tied together near the bust." The Editor then adds ingenuously that "the most elegant head covering for the retired walk is a capote of primrosecoloured Japanese gauze, trimmed in the usual way with Cheveaux de friese at the edge." It reads more like a recipe from a cookery-book than the description of a dress and a hat.

1837

Social life in London at the time of the accession and during the early part of the reign of Queen Victoria presents such a marked contrast to that of the corresponding period in Paris, that it is surprising that there is not a greater difference in the fashions of the two cities. Whilst in the French capital it has been shown that light-hearted gaiety was the prevailing note, and masquerades, carnivals, and every conceivable folly the order of the day, in England a wave of austerity appeared to have spread over the country during the previous five years. Gentility and the dullness which has been so graphically described by Dickens in his word-pictures of the time, reigned supreme, with the result that a tendency towards insipidness in every form was observable and even to a great extent in women's apparel. This insipidity undoubtedly presents a certain attractiveness, and has marked the commencement of the Victorian era with an individuality quite its own. In England feminine characteristics have always been dominated by example of the Throne. The Court has always infused, as it were, its personality into the temperament of the nation, and its manners and fashions have in consequence been more or less imitated, so there can no doubt but that the example set by the highest ladies of the land influenced the fashion of the moment.

Hence it follows that Englishwomen and the modes of this period were peculiarly representative of the temperament of the young Queen, and the surroundings of the Court. The romantic simplicity of her home life appealed strongly to the feminine imagination, with the result that there was a more decided leaning for the next few years towards breaking away from conventionality and the usual attempts to copy French fashions slavishly. One has an impression of the atmosphere of Kensington Palace or Windsor Castle in all the English styles of the early years of the reign. It was a period of harp-playing, fancy needlework, and sentimentality, inspired by the romances of Sir Walter Scott and the poems of Lord Byron; one historian even tells us that he knew many young ladies grieved because they had the appearance of being in good health, with pink and fresh cheeks, because it was "common" they said. More than one young lady, by force of wishing to look consumptive ended by becoming it in consequence of depriving herself of adequate food for fear of growing fat and material.

The quiet routine of the home life was seldom disturbed except by an occasional subscription dance and a visit to the theatre. Fashionable life, hemmed in on all sides by an awe-inspiring barrier of respectability, was naturally very restricted in its scope-it was the reign of the chaperone. Railways were still in their infancy, and the means of locomotion were wavering between the old and the new. It was a period of transition in which progress, as it is now understood, had scarcely made its way. London in the year of grace 1837 was a singularly staid and uninteresting place, yet in spite of all the conventional demureness, the love of the romantic seems to have developed the emotional character of the women of the time, and to have rendered them the more readily receptive of outward impressions. To this cause therefore one must attribute the curious condition of "sensibility" which was so characteristic of the early Victorian girl.

The favourite hobby, or rather sport, amongst the elite in Paris was ballooning, and every one who could afford it would go in for it, the ladies being particularly enthusiastic, one learns, so much so in fact, that to be present at the departure of a balloon in the morning and to be seen at a big ball at night was considered the height of "smartness." They told a story of one of these aerial travellers, a waltzer very much in repute, who commenced the evening dance early in the morning by filling up his dance programme as he stood in the car of his balloon, ready to start; his last words to a fair lady bystander, as he rose in the air, being: "Don't forget you have promised me the first waltz to-night." Sure enough he was at the ball, and no one seeing him waltz so composedly would have imagined he had been such a long journey to get to it. Paris was exceptionally gay this year.

Dancing was the order of the day, so Paris danced all through the Season. The ball at the Austrian Embassy was long talked of on account of its remarkable exhibition of jewellery. Nothing like it had ever been seen before. One wit, indeed, spoke of it as a "bal de bijoutiers." Nevertheless it was the talk of the Season. Diamonds were the rage of the year, to the prejudice for the moment of all other gems, and were worn on every possible occasion and with every grande toilette, it being said that ladies wore all they possessed and even more.

In the midst of all this liveliness, influenza made its appearance in Paris, and everybody caught it, and was laid up, but it made little or no difference to arrangements. And yet the balls went on, one danced, one tried on gowns, one had one's hair dressed, and crowned oneself with flowers between the fits of coughing. Women in the morning were shivering, sleepy, and made up into bundles of hoods, veils, and fichus, one pitied them, one groaned with them, one advised them to take a lot of care of themselves, and one left them with a feeling of anxiety-and in the evening one found them at some Ball looking radiant, head up in air, feathered and bejewelled; the shoulders nude, arms nude, and feet nude, for one could not call the spider-web silk stockings a covering. And you saw them dancing and enjoying themselves as though they were quite well again. And what did this prove? That the fashionable woman would rather die than refuse herself a pleasure, that she lived for the world, the balls, concerts, that her health was sacrificed to empty amusement, that home life with its sameness and boredom no charm for her.

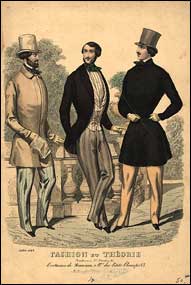

1838-1840

The Parisienne at this period presents a curious study of insouciance. Extravagant in her toilette to a degree which had never been surpassed, her Salons furnished with a magnificence that amazes one even now in these twentieth-century times, she yet lived in the midst of a curious combination of luxury and coarseness. It was a time when everything, to be quite the "ton" had to be sporting, and therefore, to be the real "sportsman" the men dressed themselves as much like Englishmen as they always imagined them in those days, the resulting that they generally looked like stablemen, and it was considered not at all bad form for a gentleman to pay a visit to a lady attired in his riding-suit, covered with dust with dirty top-boots, and reeking of tobacco. It was a sure proof that he had just returned from the Bois, and therefore this negligence in his costume was quite pardonable. His hostess, however, would receive this grotesque, and unclean individual in her dainty salon or boudoir, garbed most probably in the most bewitching costume, the very latest creation of Palmyra or Herbaut. One cannot nowadays comprehend the peculiar apathy of the women of that time, condoning such unpleasant idiosyncrasies. This slovenliness was carried even furthur in the evening, for men appeared at balls or receptions in the most unconventional costumes, and wearing lace-boots. The contrast between the sexes in the world of fashion at this period was very curious.

1840-48

The fashions of the moment in Paris were more accurately represented by the wealthy middle classes. Still the sedate old patricians were not averse to their young folk amusing themselves in their own set, and cotillons were the order of the day in the winter, whilst in the spring and summer, garden-parties and "dejeuners dansants" were the rage for a time. At these dejeuners dansants, all the aristocracy of Paris were to be seen. Those given by the Comtesse Appony were the most famous, and from all accounts they must have been wonderful scenes as there was quite a bevy of elegance and beauty. The guests were invited at half-past two in the afternoon, and the dance took place therefore in daylight. The long lines of waiting carriages, the resplendent liveries of the servants, all the wonderful spring toilettes, with their simple adornment of flowers or ribbons, in contrast to the diamonds and sapphires of the winter ball-dresses, combined to make a picture which was not easily forgotten. Immediately on entering the house each lady was presented with a bouquet of flowers. Dancing commenced punctually at the time fixed, the valse a deux temps being especially the rage at that time. Towards four o'clock there was an interval for "lunch" which, when the weather permitted, was served at small tables in the gardens. After this dancing was resumed, and continued until nine o'clock, when the party broke up.

With gay and fashionable society, and the masses in the right mood to condone and even applaud any eccentricity, it is not to be wondered at that female fashion reflected the general atmospheric gaiety, and during the next few years was witnessed in Paris a sort of repetition of the frivolities of the Directoire period. It became fashionable for smart women to give Adamless luncheon-parties in their apartments. On these occasions they attired themselves in the most gorgeous of deshabille—these luncheon gowns being often quite chefs-d'oeuvre of the dressmaker's art. After lunch cigars were usually handed round, and when these and sundry liqueurs had been enjoyed, riding-habits were donned, and the remainder of the afternoon was spent in the open air in the Bois and elsewhere; for these elegantes added physical attainments to their other attractions, and many of them were good shots and expert fencers.

1851

The year 1851 was remarkable in London; it was the year of the Great Exhibition, and the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park was the scene of gaiety and splendour such as had never before been witnessed in England. The Exhibition was opened on May 1 by Queen Victoria in person, and was closed on October 11 following, and its success was so great that it proved the forerunner of many other exhibitions all over the world. As was only natural, this year of gaiety was to be followed by several dull and uneventful Seasons, in which fashion was in a state of transition, hesitating, as it were, between a return to a more simple mode or the adoption of the "Hoop" which was foreshadowed by the deliberations of the French autocrats of fashion.

The year 1851 was marked by the attempted introduction into England of the American idea of a dress fanatic obsessed on the subject of a rational costume for women. No description of this period would be complete without some mention of the notorious lady who had the courage to attempt to bring about such a drastic innovation in a country which was not hers by birth, and where she was only known in connection with her failure to bring the women of the United States into line with her views.

We are told that the first man who carried an umbrella was mobbed through the streets of London. The first lady who assumed "pantalettes" became at once the object of vulgar curiosity and idle gossip. The lady in question was a Mrs. Bloomer, the editress of an American publication, and a person with strong views of her own as to feminine attire, which she had come across from America; especially to put forward, realising doubtless how true is the adage that none can be a prophet in his own country. Her proposed revolution in female costume was not, however, taken more seriously in England than over in the States, but for a short period Mrs. Bloomer achieved quite a notoriety, whilst curiously enough the actual article still exists as a female garment, and is known by her name.

The movement she endeavoured to initiate excited so much controversy and amusement at the time that it will be of interest to give some account of it. It was known also as the "Camilla" costume, and the main features which distinguished it, we learn from "Sartam's Magazine," a popular monthly periodical published at Philadelphia, were short skirts reaching just below the knees and long pantalettes. Its adoption was advocated on the ground of comfort, health, and unimpeded locomotion. All matters of detail, proportion of parts, materials, trimmings, etc., were left to individual taste. There was already, said Sartam, as great a variety in Philadelphia in the new costume as in the fashions imported from London or Paris. The reason, it continued, was evident. "A lady who is independent enough to disregard the attention such innovations necessarily attract, will also be independent, enough to vary them to suit her fancy. Some of the dresses are therefore very elegant and graceful, while others are clumsy and gaudy".

Meanwhile Mrs. Bloomer's adherents used their utmost endeavours to bring the English public to their way of thinking, and to this end, in London, Dublin, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, ladies, singly and in pairs, appeared publicly in the new costume, but the wearers were not sufficiently nerved to withstand for any length of time the persecuting curiosity aroused by the strange garb, although fourteen ladies so attired, and accompanied by as many gentlemen, calmly paraded the streets of Philadelphia without being molested. A prominent American journal remarked that; had Queen Victoria and her Court donned Bloomer attire, the example would have been spread fast enough. This might perhaps have been the case, on the same principle as the farthingale became the mode in Queen Elizabeths time, but there was no such incentive.

Lectures were given in London and Dublin on and in the new costume, but at one which was announced as being given for the special benefit of the people of Finsbury, the conduct of the audience was so boisterous as to intimidate the lady lecturer, who deemed it prudent not to appear. It was ascertained afterwards that there was not only no fear of her not receiving a fair hearing, but that the majority of the audience was determined she should not have been annoyed. The following letter appeared in the Daily News next day: "SIR,—May I be allowed in your columns to ask why the British public is so horrified at the idea of women dressing in trousers, seeing that they have for many years tolerated a number of men from the North of the Tweed in wearing petticoats, and shockingly short petticoats too? AMELIA BLOOMER."

The agitation of Bloomerism continued with unabated vigour. A committee of ladies was formed, and lectures were given at Miss Kelly's Soho Theatre, the Linwood Gallery in Leicester Square, and in other places, A ball was announced at the Hanover Square Rooms,at which all ladies were requested to wear Bloomer costume. The lecture at the Soho Theatre, says a London paper of the time, was crowded, and an attempt at interruption by some hilarious individuals was immediately suppressed. The lady lecturer who appeared in the costume was accompanied on to the platform by several other "Bloomers", as they were jocosely termed by the crowd. Coming straight to the point, however, the lecturer told the audience that the movement was not dictated by any freak of vanity, nor was it started from any personal motives; it was purely from the standpoint of public morality that it was undertaken. The American women who had taken the lead in this reform were those who had taken the lead in another of the greatest reforms of the age—the question of American slavery (loud cheers). The lady was in the midst of her disquisition, when eight more young ladies entered most oddly attired. The audience found it impossible to maintain its composure, and burst forth into a genuine shout of laughter, a proceeding which seemed for a moment to daunt the fair lecturer. Another lady in semi-Bloomer costume now came in front of the stage, and begged a fair hearing for the American lady.

The lecturer continued, "in their investigations the women of America found that they had one despot in the way, one that refused to be questioned either by morality, religion, or law; that tyrant was known to the world by the name of Fashion; that tyrant the women of America had determined to bring before the bar of public opinion on three special charges. First, that nature had been violated, its rules and life endangered; second, that in consequence of its requirements a vast amount of money had been expended which might have been diverted to higher and holier purposes; and third, that by encumbering women it incapacitated them from rendering services to society worthy of their high destiny. These doubtless were strong charges, and for them she hoped the tyrant Fashion would receive either banishment or transportation for life." The lecturer then went fully into the familiar question of stays, and their deteriorating effect upon the human frame. She implored the women of England to follow the example of America, and no longer countenance such an atrocious system. She confessed that in many parts of the country the Bloomer costume had been received with much disfavour, but so had paletots when they were first suggested for ladies' wear. The lecturer concluded by thanking her audience for the treatment she had received, and the audience responded by giving her three cheers.

The daily and weekly papers all gave the question their attention. The "Medical Times" said: "An essential in the Bloomerian creed is no corsets. That banner we nail to the mast, and so far heartily give our support. For many a weary year have medical men been preaching a crusade against stays, and in vain endeavoured to stem the tide of fashion which sets so strongly in favour of them. In spite, however, of all that has been written and said upon the subject, and in spite of the sacrifices of the hundreds who have fallen victims to this odious fashion, the public have obstinately turned a deaf ear to our remonstrances. The tide may be about to turn. Mrs. Bloomer may cause it to run the other way, and we hope for her success. As regards the other part of the dress, the idea of females having trousers may be scouted as ridiculous, but as nine out of ten do happen to wear them, the fact of their being an inch or two longer can make no difference, and it becomes a mere question of common sense whether a costume which clothes the body well and yet allows free play to every part, is not a more rational habit than a pinched-up, wasp-like waist, and a cumbersome mass of horse-hair, hoops, furbelows, and flounces, sweeping the mud in the streets, and doing part of the duty of Mr. Cochrane's orderlies, whilst they also evoke the anathemas of the gentlemen, as when following ladies downstairs they tread on their dresses, trip, swear, and apologise."

Many tawdry coloured prints with dismal attempts at verse attached to them were sold by street-hawkers, and Madame Tussaud added a group of figures in the Bloomer costume to her exhibition; but as was inevitable, the much-talked-of revolution in female attire was killed eventually by ridicule and satire. It had been started at least fifty years too soon, as one now sees. A sort of obituary notice of it which appeared in one of the daily papers may be of interest in concluding this account of Bloomerism. "The disadvantages of the dress," they said, "are its novelty—for we seldom like a fashion to which we are entirely unaccustomed—and the exposure which it involves of the foot, the shape of which in this country is so frequently distorted by wearing tight shoes of a different shape from the foot. The short dress is objectionable from another point of view, because, as short petticoats diminish the apparent height of the person, none but those who possess tall and elegant figures will look well in this costume: and appearance is generally suffered to prevail over utility in consequence. If to the Bloomer costume had been added the long under-dress of the Greek women, and had the trousers been as full as those worn by the Turkish and East India women, the general effect of the dress would have been much more elegant, although perhaps less useful. Setting aside all considerations of fashion, as we always do in looking at the fashions which are gone by, it was impossible for any person to deny that the Bloomer costume was by far the most elegant, the most modish, and the most convenient." Women in England, however, who wished to retain some appearance of femininity decided otherwise, and, judging from the unlovely picture of Mrs. Bloomer which is here given, it is probable that most people in our days will endorse their verdict on the so-called "rational costume."

1851

We now approach a period which marks a boundary line as it were between elegance and disfigurement in the history of feminine attire. For some years there had been a noticeable disposition towards making a drastic change in the fashionable dress. It had been confidently anticipated that the advent of the Second Empire would bring about a return to the delightful costumes of the Consulate, but this anticipation was not destined to be realised, Dame Fashion had another surprise in store.

For the first two years of the new regime, woman's dress remained practically in status quo, that is so far as one can apply the description to anything feminine. At any rate, the modifications did not amount to anything in the nature of a complete revolution such as was on the tapis, and there was a slight tendency towards a definite return to the bodices and the straight waists of the eighteenth century rather than to the classical of the First Empire. When, in 1854, there came the edict of the fashionable dressmakers that the skirts which hitherto had been worn wider round the hem were, if anything, to be increased in circumference and stiffened, the inauguration was made of the ugliest mode the world has probably ever seen. The suggestion, first of all, of the new style was to make the wearer look more corpulent, or rather to leaven the outward appearance of the plump and the thin; and secondly, that, the ordinary skirt being too limp to support the flounces then the fashion, it became necessary to add some internal stiffening to hold them out. Highly starched linen petticoats were tried for a time, but without achieving the result aimed at, then the dressmakers remembered the material known as " crinoline which had been used during the thirties for keeping the "manches a gigot" in position. Once started, it was discovered that merely stiffening the skirt with the horsehair cloth still did not give it the necessary resistance, so an inventive individual evolved a combination of hoops of steel and steel springs which transformed the skirts into veritable cages, almost identical in appearance, save for a few modifications, with that of our old-friend the farthingale of Queen Elizabeth or the hoop of the Louis XVI period. The crinoline was therefore but the revival of an ancient mode under a new name. Women of fashion the world over, whilst realising the ridicule the new fashion would bring upon them, nevertheless decided to adopt it, and having done so, stuck bravely to their convictions with a force of character and a philosophic indifference to the quips and satire of the moralists and doctors, and the low jokes of music-hall artistes that quite surprises one nowadays. They continued, to wear the crinoline, in spite of all this, with genuine feminine perversity, and it is difficult to believe that any woman in her senses and with an atom of pride in her appearance could have thought that the hideous arrangement, when in the zenith of its ugliness, could by any stretch of the imagination be considered becoming or attractive. Whole volumes might be written on the subject of this extraordinary innovation. It was the source of endless discussion, and eventually brought into existence two distinct factions in the world of fashion. In France, especially, war was waged between the two parties with undisguised bitterness, the anti-crinolinists even going so far as strongly to advise the adopters of the mode to stick to it, as it gave them a good chance of disguising their bad figures at any rate.

One of the most prominent opponents of the crinoline in Paris was the beautiful Madame de Castiglione, who always appeared at the State balls at the Tuileries in clinging drapery, in open disregard of the fashion of stiffened flounces set by the Empress, who, whilst not actually a wearer of the hooped skirt, had always had a penchant for puffings and paddings and frills and innumerable petticoats. In this connection it may be of interest to relate that the Empress, who was, as we have already stated, looked upon as a leader of European fashion, decreed that white tarlatan should be the evening mode at balls, where the steels of the crinolines would have rendered dancing or even locomotion so impossible. The women expanded their skirts by wearing a dozen or more starched flounced petticoats at once. When it is mentioned that, for a double skirt of three flounces, fifteen yards of material thirty-six inches wide were required, one can form some idea of the extravagance of the new mode.

A big industry gradually developed in connection with the manufacture of steel springs for crinolines, and one can in a measure grasp the extraordinary proportions this vogue attained when one learns that in the report of the French Jury at the London Exhibition of 1854 the annual production of steel crinoline springs for the world was 4,200,000 kilogrammes, valued at 10,500,000 francs, out of which huge amount France alone was responsible for 2,400,000 kilogrammes, and England for 1,200,000 kilogrammes.

The steel hoop or cage did not, however, enjoy a prolonged period of favour. Its manifest unfitness was soon too obvious to be disregarded. It was too hideously rigid, and moreover, by reason of its unresisting rigidity, was often the cause of involuntary indecency on the part of the wearer. It was therefore abandoned in favour of whalebone after a time, and subsequently both were superseded by a number of heavily starched linen petticoats for outdoor wear, which were found to answer the purpose equally well.

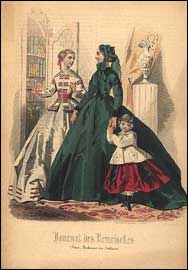

1862

In 1862 London's second great International Exhibition was held in a building erected close to the Horticultural Gardens in Kensington, and attracted; if anything, more people to the Metropolis than the previous one. The idea had caught on, and there were talks of a series of exhibitions in the various capitals of Europe during future years. At this moment the crinoline, with all its hideous paraphernalia, was at the height of its absurdity, and the scenes witnessed in London amongst the crowds, of visitors attracted by the Exhibition have been described as surpassing in pure extravagance of ugliness anything that had been seen before in the world of woman's dress. Nor was there any sign at this period of any growing sense of humour on the part of misguided woman with regard to her appearance, and the ludicrous effect it produced. The strange fascination the steel cage exercised over the feminine mind is one of those psychological mysteries which can never be satisfactorily explained. But to the mere man and to the artist it is utterly incomprehensible how any woman, endowed by nature with natural physical charms, can, at the mere dictates of a coterie of dressmakers, will-fully disfigure herself.

1865

Fashion, ..., as represented by society, stood for almost everything that was bright and amusing in those dull days of the sixties. During the "season", which was in the summer months only, the rendezvous of the elite was Hyde Park between the hours of five and seven. Rotten Row was then crowded with equestrians, whilst the "mile", the stretch of roadway between Hyde Park Corner and Knightsbridge Barracks, was then blocked with magnificent equipages, and this show of horseflesh alone was always spoken of as one of the sights of Europe. The strip of gravelled walk between the Row and the "mile" was the favoured point of assembly for those who were not driving or riding, and the numerous chairs were always occupied by a throng which resembled a big family, as every one seemed to know every one else. The defile of carriages with their smartly dressed occupants represented all the wealth and beauty of the London season, but although fashion was there, it was evidently not such an exhibition of style as Englishwomen in their artlessness were wont to believe.

Monsieur Taine, in his interesting "Notes sur 1'Angle-terre" in the late sixties, thus gives his impressions of the scene: "From five to seven, review of toilettes; beauty and finery abound. Colours are outrageously crude, and the figures ungraceful. Crinolines too hooped, and badly hooped, in lumps, or in geometrical cones; green flounces, dresses with gold embroidery, flowered dresses, a profusion of light gauze, masses of hair, curled and hanging loose, crowned with small hats covered with flowers; the hat is over trimmed, the hair too shiny and sticks severely on the temples. The mantle or the cloak falls shapelessly over the hips, the skirt is absurdly puffed out and the whole effect is bad: badly chosen, badly made, badly arranged, badly put on and the load colouring simply skrieks out".

1865

In 1865 the principal papers of Paris thus described the dress worn by a well-known society beauty and leader of fashion at a Court ball at the Tuileries: "A white dress, composed of alternate bands of tulle and satin over a petticoat of tulle with silver stripes and garlands of roses, sewn with little stars and spots of black velvet; a very long train of black velvet trimmed with satin; a belt of emeralds and diamonds; an Empire coiffure powdered with gold-dust ; and a velvet ribbon round the hair holding a diamond aigrette; no crinoline." The significance of the last two words cannot be over-rated, for they sounded the death-knell of the crinoline.

In the meanwhile, whilst waiting for the auspicious moment, a craze for colour had come over the scene which accentuated still further the hideous taste of the period, and which made one seriously wonder whether for a time women had not taken leave of their senses, for this is the only charitable inference one can draw after an inspection of the fashion-plates of these years. There are doubtless many people still living who can remember the awful patterns and colours of the sixties: the plaids, the checks, the stripes, and the magentas, the solferinos, the puces, the violets, the bright blues and greens, which were seen in merinos, Irish poplins, and English alpacas, all so shockingly crude as to be positively nauseating to one nowadays, but little did that matter in that lamentable decade, when good taste was generally non-existent, and when apparently nearly every woman was striving to outdo her neighbour, not only in the loudness of her dress, but by her wild extravagance in the feverish desire to attract attention at any cost.

One must not omit at this juncture to record another and still further barbarism which also marks this period indelibly; this was hair-dyeing. Yellow or red hair now became the rage. It is said that this mode arose from the desire of the smart women in Paris to copy the Empress as closely as possible. The difficulty in this case was in getting anywhere near the wonderful shade of her hair, which has been described as neither blonde nor red nor auburn, the secret of which, if there was any secret at all, she alone possessed; and this perplexity accounted for the many disastrous results.

Every one, however, whose natural colour was brown or black and who desired to be considered in the fashion, had to proceed to her coiffeur and leave herself in his hands. This dyeing was, of course, an expensive process, but the result quite justified the means in the opinion of the elegantes, although they frequently had to run the gauntlet of the jeers and laughter of the crowds in the streets, to whom the transformation was as often apparent as it was diverting, for at that time hair-dyes and bleaches were not always successful. The chemists had not yet discovered the secret of making natural tints, with the result that not infrequently the coiffure of the up-to-date lady of fashion, after a visit to her hairdresser, presented quite unaccepted shades in the range of capillary colouring. There was a peculiar tone of deep yellow, which was particularly crude and horrible to look at if not successfully produced.

The day of the Grand Prix at Longchamps was then, as it is still, the big final event of the Paris season, and thousands were attracted to the famous racecourse who knew they had not the remotest chance of seeing any of the racing, so great would be the crowd on that particular day. Still, all who could get away from the stifling air of the city on this particular Sunday would make their way to the Porte Maillot, if only on the chance of catching a glimpse of some of the celebrities of the day-perhaps the Emperor and the Empress, if one was lucky; if not, some of the fashionable beauties and well-known demi-mondaines.

The endless defile of carriages of every possible description with their loads of well-dressed and interesting people, from the splendid four-in-hand to the ordinary sapin or cab, was a source of never-failing interest to the less fortunate individuals who considered themselves as forming part of the procession, by crowding at every corner and criticising loudly and with much good humour and ready wit all who attracted their notice as they slowly drove past. The grandes demi-mondaines, those fair and frivolous charmers who were so much en evidence in the world of fashion during this epoch, were always the cynosures and to a certain extent the favourites of the public. One heard quite a chorus of recognition when such well-known beauties as Leonide Leblanc, Anna Deslions, Cora Pearl "la belle Anglaise," Marguerite Bellanger, and Marie la Polkeuse, to name only a few out of the score of pampered Aspasias whose names were household words in the world of pleasure in Paris in the 'sixties, rolled by in their magnificent equipages.

1875

Hair was still worn high with ends and undulations over the forehead; or with chignons a l'Anglaise. There was also another somewhat favourite; mode a la Marguerite in "Faust" with the hair very simply arranged in front, with two long plaits hanging down the back. This style was supposed to give a Juvenile appearance, and was therefore more often adopted by women no longer in their premiere jeunesse. One must not omit to mention the prevailing custom in these years of wearing false hair. It was a recrudescence to the fashion of the beginning of the century, and an important industry gradually arose in connection with it. Trade statistics tell us that in France, in 1871 alone, 51,816 kilogrammes of human hair were sold, 85,959 in 1872, and 102,900 in 1873. We have no figures for subsequent years, but the total must have considerably increased considering the fashion. Marseilles was the principal depot and port of entry for the trade in human hair. More than 40,000 kilogrammes weight was imported annually. As the weight of hair in an ordinary chignon did not exceed l00 grs., the quantity imported annually would be sufficient for 180,000 of these head-dresses. There was a celebrated house in Paris which did not sell less than 15,000 chignons a year at prices ranging from 12 to 70 francs each, but there were some costing as much as 250 francs. The hair came practically from all over the world, though the various nationalities had different values. The French provinces which furnished the most were Brittany and Auvergne. Cutters went round to the different villages and fairs to collect it in exchange for shawls, dress material, or toilet articles. They would also pay cash at the rate of about 5 francs the kilo. Their arrival at the several market centres always took place at the same time of the year. They had no need to advertise their coming, in fact they had no sooner taken up their quarters than their flocks gathered around them, willing and eager to be shorn. And all they had to do was to reap their harvest and conclude their bargains as speedily as possible. The young girl who desired to sell her head of hair got up on to a cask, and, undoing her coiffure, let it fall over her shoulders. Then a lot of amiable bargaining took place between her parents and the marchand. The deal concluded, the cutting part did not occupy many seconds, and both parties were satisfied. The women did not, however, submit to actual denudation of the head, but reserved a small portion of the front, which, by clever arrangement, was afterwards so disposed as in a great measure to conceal the ravages of the scissors. The actual operation was managed with extreme rapidity, and as soon as the hair was cut off, it was tied in a wisp, weighed, and the bargain concluded.

A great deal of hair was sent annually from Italy, and more particularly Sicily and Naples. Red and golden hair, which came principally from Scotland, were the most costly. The number of chignons exported from France to England in 1875 was 16,820, with sufficient hair to make up another 11,000. The United States came next on the list. It may be of interest to mention a fact that will upset a popular fallacy: hospitals do not supply the hair used for wig or chignon making. No hair cut after death is of any use to the wig-maker or coiffeur. In other words, it must be live hair, otherwise it is brittle and cannot be curled and adapted into different shapes. Another curious fact is that masculine hair has no value whatever, and is useless for even making mattresses.

1887

With the opening of the Savoy Hotel in 1887 may be said to have commenced a new era in the life of fashion in London. Up to that time the Metropolis of the world was ill provided with places where entertaining on a large scale was possible, the good hotels and first-class restaurants being too small and badly appointed to be able to cater for such festive gatherings, whilst the second-rate ones were little better than glorified railway inns. With the advent of the Savoy a new feature was introduced in society entertainments. The larger and more brightly decorated restaurant, run on French lines, which caters not only, for business folk in the day-time, but makes a point of attracting ladies for dinners and suppers, now became an institution.

The shrewd French restaurateur has long realised that to a smart woman the opportunity of displaying her toilette to advantage is of far more consequence than food, for women are not gourmets by nature. Realising, therefore, that, by pandering to her vanity, she would unconsciously help to advertise him, he engages the cleverest and most up-to-date architect, to whom he confides his ideas, with the result that entrances to lobbies in restaurants are designed with a view to giving the elegante a suitable entree which commands the attention of the whole assemblage. Dressed in the latest creation from Paquin or Laferriere, it is obvious that she does not want to make her entrance unnoticed. Before 1887 London fashionable life was the life one led at home, entertaining was done privately. Since those days society has made big strides towards Continental ideas, and to its advantage, as will be admitted by all who can recollect London in the seventies and early eighties. The type of the woman of fashion has also altered, and beyond recognition during the past twenty-four years. She has emancipated herself from all the silly narrow- mindedness which was the life burden of her grandmother when a girl. Society may be no better now than it was in those far-off days, for human nature remains unchanged, but it is certainly no worse, and without a shadow of doubt it is brighter and more intelligent. Class prejudice still exists, but it is becoming yearly less noticeable.

In what one may term the pre-Savoy days, for an unmarried lady to be seen dining at any restaurant frequented by actresses was tantamount to losing her reputation, and no man would have ventured to invite a lady to any place where such "low creatures" were likely to be seen. Now, in all the big restaurants and hotels, not only do the belles of the beau monde rub shoulders with the ladies of the stage, but also with the "gilded beauties" of the demi-monde, and they do not appear to be outraged when this happens.

What has brought about this change, this volte face? A variety of causes. In the first instance, the opening of al-fresco entertainments in the summer, on Continental lines, where people can congregate and listen to good music and harmlessly enjoy themselves. In England it takes a long time to upset preconceived notions, and the mere suggestion of the opening of such places as the Horticultural Gardens immediately recalled visions of the results of previous so-called open-air entertainments, which had degenerated into mere resorts of vice and rowdyism.

The "Health Exhibition" in the Horticultural Gardens at this period proved an unparalleled success, and the beautiful, brilliantly illuminated grounds were crowded every evening with well-dressed and orderly people, who evidently appreciated the innovation. There was no sign whatsoever of the old degeneracy in this new undertaking. The Horticultural Gardens, though eminently adapted for this kind of entertainment, were, however, required for the buildings of the Imperial Institute; the Earl's Court Exhibition was therefore opened early in the nineties, and jumped immediately into public favour. The spacious grounds proved an excellent locale for the al-fresco entertainments which London was now beginning to expect in the summer months. Open-air cafes and restaurants, quietly and decorously conducted, became a standing reproof to the assertion that Continental ideas are not adaptable to England, and to the old-fashioned, narrow-minded prudes, whose contention has always been that the morality of the nation can be improved by keeping the sexes rigorously apart. The orderliness and the simple, unaffected enjoyment of the crowds in the gardens have always been the subject of astonished comment by all the foreigners visiting London during the summer.

Emboldened by the success of the open-air entertainments, Sir Augustus Harris decided to carry out a long-cherished scheme of his, namely, the introduction of balls costumes at Covent Garden Theatre, on the lines of those held in the Opera House in Paris. They were an instant success, and during the first years of their existence were the rendezvous of the smart set. Masks and dominoes were much worn, and many were the intrigues which found their inception in the boxes and corridors of the spacious theatre, and for several years these balls enjoyed quite a vogue in the fashionable life of London.

Another reason for the great change one notes at this period from the staid gentility reminiscent of the mid-Victorian times to the more light-hearted Continental tendency, was brought about in no small degree by the advent of the bicycle for women. In respect to the bicycle, it was somewhat surprising that, although England had always been the leader in outdoor sports and athletics, it should have been across the Channel that women first took up bicycling. The Parisienne has always been keen on new pastimes and fresh sensations, and therefore the bicycle, which had hitherto been regarded as a purely masculine form of-exercise, was introduced in a new role as an attractive recreation for women. It caught on at once, and was not long in establishing itself firmly in favour, not only with young women of fashion, but with every woman and girl who was fond of exercise. The early part of the nineties, therefore, saw the bicycle the rage of feminine Paris.

The new machines differed in no particular respect so far as build was concerned, except in weight, from those ridden by men. Consequently they necessitated riding astride, and in a costume which put the sportsmanlike character of the Parisienne to the test. Anything more inelegant could not be conceived. It consisted, generally, of a very wide pair of knickerbockers not unlike bloomers in shape, stockings, and high boots or shoes, a simple shirt with collar and tie, and a soft felt hat with no trimming, but placed on the head with that "chic" which only a Parisienne can apply. Nevertheless in this ungraceful garb, when spinning skilfully along the country roads, she presented a thoroughly sportsmanlike appearance which was not without charm.

In England, women, with somewhat strained ideas of propriety, never dreamed of bicycling till they were offered machines specially adapted for them. Without the introduction of the low, open frame, and the practicability of riding in ordinary costume, it is probable that bicycling would never have become popular in England. From the moment that it was conceded that a lady did not necessarily lose caste because she rode a bicycle, the emancipation of the fair sex began. The rage for bicycling which was the feature of the London season of 1896 will not be forgotten. The sight in the Park every morning from eleven till one, when the road from Hyde Park Corner to the Magazine was packed with cyclists, amongst whom were all the ladies of smart society in England, was epoch-making in the history of feminine fashion. The fashion for cycling in Hyde Park died out as might have been expected. Women, once their sporting instincts were aroused, soon got sick of wheeling up and down a comparatively short road merely to be seen, and besides which, the amusement was becoming "common". But the impetus had been given, and the results could not be withheld. It was one of the stages in the evolution of the modern woman of fashion, and otherwise.

In respect to golf, which also exercised a very considerable influence on the character of the modern woman of fashion, its correlation to the bicycle appears to be evident, as without it many of the links now comparatively within easy riding distance would be accessible only by tedious railway journeys. As is well known, for many years prior to 1896, ladies played golf at St. Andrews, North Berwick, and several other places where there were small links. Many clubs reserved special places where ladies could play. Gradually, however, it was recognised that such restrictions were unnecessary, so now ladies play everywhere, and their championships take place on ordinary links where exceptional skill and knowledge of the game are essential.

Dress reformers, under the leadership of Lady Harberton and her followers, had attempted sixteen years previously to do what the bicycle now achieved without self-advertisement. The hygienic costume which was considered so outre as to cause her ladyship to be forbidden admission to many restaurants and hotels, was now gradually reintroduced in the guise of the divided bicycle-skirt, and although at first it was looked at rather askance by country innkeepers, it was eventually accepted in quite good faith as indicative of "sporting"and not "fast" instincts in the fair wearer.

With the appearance on the scene of a new social life, as it were, the world of feminine fashion underwent a remarkable series of changes. The languid elegante of the old-fashioned school became transformed into a new being, a modern creation evolved from modern ideas. Not content with joining issue with man in open-air sports, she must have, like him, a club, where, in a privacy that should be different from that of her home life, she could write her letters, receive her friends, male and female, and, if so desirous, remain perfectly undisturbed as long as she wished. It was this that prompted the foundation of the Alexandra Club in 1884, the Empress in 1897, the Lyceum and the Ladies' Army and Navy in 1904, and many others since. With the change in her ideas there was also an accompanying reaction in her notions of fashion. The tailor-made costume had begun in 1888 to make steps towards an elegance of line and finish which was somewhat unexpected. Ladies' tailors were now to be found in increasing numbers, fully proving that, with the bicycle, other outdoor sports were also claiming the attention of the fair sex, and thereby necessitating special costumes. For morning wear, men's tweeds and cheviots were the correct thing, even on occasions where more dressy costumes would have, a few years previously, been de rigueur. With this practical costume many of the smart women would carry out the male effect to the extent of wearing a shirt of masculine appearance, with stiff collar and tie. The effect was unwomanly and calculated to impart a hard, sporting appearance to an otherwise gentle, ladylike demeanour; it had, however, a considerable and popular vogue for some years, and long after it had been abandoned by the leaders of fashion, till it was ousted by the "jabot" and the more distinctive feminine embellishments of lingerie.

In the meantime a serious rival to the bicycle in popularity with the fair sex was rapidly coming to the front in England. This was the motor-car, which was destined still further to revolutionize feminine fashion. In the first few years of its existence it was looked upon as more in the nature of ah engineering freak than as a vehicle with any potentialities.

Women were, ... [wary] of trusting themselves in the evil-smelling, noisy, and uncouth-looking machine, so for a long time it remained outside the domain of amusement so far as they were concerned. Combustion engines were meanwhile being gradually perfected. Attractive coach-building and upholstering combined to bring motoring as a luxury more tangibly to the notice of the up-to-date London society woman as well as the smart Parisienne, with the result that by the end of the century this new mode of traveling had so fascinated them that already many had cars of their own.

1906

About this time an American black-and-white artist, Dana Gibson, had come very much to the fore with a type of up-to-date American girl of his own conception; this type became immediately popular, and the Gibson girl was at this moment as much in vogue as was the du Maurier girl of the early seventies. His drawings are too well known, however, to need more than this passing reference, but as inaugurating a distinct type of the period, they cannot be omitted in a description of feminine fashion. The American girl, a product of an advanced and comparatively young nation, embodies in her type charming characteristics which give her a marked individuality, quite of her own, and these have been most ably caught by her clever interpreter.

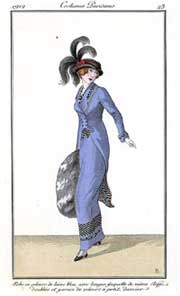

1910

In England, as we have already remarked, the mode is usually represented by the jeunes filles, and nowhere is this mode more delightfully manifest than up the river during the season. On a fine Sunday morning. Boulter's Lock presents a spectacle of youthful beauty and becoming costumes, which has always excited the admiration of the visitor from abroad, and which-no other country in the world can equal. If she has any pretensions to good looks and figure, the English girl looks positively bewitching when reclining amidst soft cushions in a punt, and the most simple dress then appears more attractive than the most up-to-date French creation.

Ascot holds its place par excellence as the smartest and most fashionable function of the London season, and, for elegance and beauty the scene in the Royal Enclosure or the Paddock on Cup day certainly equals anything the Continent can display, whilst the coup d'oeil is probably unsurpassed by any other racecourse in the world. Longchamps, Auteuil, Chantilly, or Maisons Lafitte present scenes of fashion pure and simple, which are undoubtedly most attractive, but for aristocratic elegance Ascot is unapproachable. Regatta week at Cowes shows us the English society girl in another-aspect. See her in the High Street on a breezy morning, in her trim tailor-made blue serge suit and simple straw hat or cap, with the wind tossing her fair hair and imparting the blush of health to her cheeks, and you see the personification of the daughter of Neptune. It is thus especially that the English girl holds her own triumphantly against all comers.

1912

With the conclusion of the first decade of the twentieth century the world may be said to have entered on a new era, an era of hustle and excitement, when every year practically brings forth some new cause for amazement or an eight-day wonder. What in 1912 appear as trivialities would have been considered events five-and-twenty years ago. The result of continually living at high pressure has reflected itself not only in feminine fashion, but also in feminine character. In the feverish rush to get through her engagements, the modern elegante has but little time except for dining in restaurants, motoring, bridge, and week-end visits. In the most giddy times of the Second Empire she never lived at so rapid a pace as she does now.