The Lushootseed Peoples of Puget Sound Country

This site includes some historical materials that may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the Collection authors in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

Essay by Coll-Peter Thrush

-

Topics:

- Introduction: The People of Huchoosedah

- Making the World as It Is: The Transformer Stories

- Figures in the Landscape: Spirit Powers and Religious Traditions

- Circling through the Seasons: Gathering Wealth from Land, River, and Sea

- Weaving a Life Together: Body, House, Community, Cosmos

- The World Changes: The Coming of Europeans and Americans

- Into the 21st Century: Survival and Adaptation

- Bibliography

- Study Questions

- About the Author

Introduction: The People of Huchoosedah

The Native Americans of Puget Sound have been known as Puget Salish and Southern Coast Salish, and by various spellings of tribes and reservations such as Duwamish, Nisqually, Skagit, and Snoqualmie. In this essay, they are called the Lushootseed peoples. Lushootseed comes from two words, one meaning "salt water" and the other meaning "language," and refers to the common language, made up of many local dialects, that was spoken throughout the region. (See also: "Snoqualmie-Duwamish Dialects of Puget Sound Salish".)

Lushootseed territories covered a large part of what is now western Washington, from near present-day Bellingham south to the state capital of Olympia, and from the Cascade Mountains west to Hood Canal. Their northern neighbors were the Lummi and Nooksack peoples, while the Twana, Chimacum, and S'Klallam lived to the west. The Chehalis lived to the south, and the Cascades formed a boundary, crossed by high mountain trails, with the Yakama and other peoples of the Columbia Plateau.

Lushootseed culture has often been overshadowed by the "totem pole cultures" of the Northwest Coast and the "tipi cultures" of the Great Plains. However, for those who look and listen, Lushootseed traditions are as rich as the bountiful land around the shores of Puget Sound. The core of these traditions is Huchoosedah, a term meaning cultural knowledge and knowledge of self. This essay views Lushootseed culture through the lens of Huchoosedah, which has been an anchor for Native people in Puget Sound country during two centuries of great change.

Making the World as It Is: The Transformer Stories

From archaeological sites, scientists know that Native Americans have lived around Puget Sound for over 10,000 years, arriving just after the Ice Age. Lushootseed origin stories also place the creation of their world far in the past, when the world was in flux. Most of these stories focus on a figure called the Transformer or Changer, whose actions gave sense to the Lushootseed world.

In the Star Child story of the Snoqualmie people, for example, two sisters camped in a prairie to dig the bulbs of the camas plant. As they fell asleep, the younger sister wished that two stars in the night sky would become her and her sister's husbands. When the sisters awoke, they found themselves in the Sky World as the wives of these two stars. Soon, the older sister had a son, the Star Child. But the two sisters had begun to miss their home. Digging in the Sky World's prairies, they broke through the ground and saw their home below. They wove a ladder of roots and when it was long enough, lowered themselves down to the earth. Upon their return, there was a great celebration, during which the Star Child, now known to be the Moon, was carried away by the Dog Salmon People. Several local heroes like Jay and Osprey tried to find him, to no avail.

Years later, Moon returned to his mother's people. Along the way, his powers as Transformer changed the world. After a moment of indecision, he made the Salmon go both up and down the rivers. He came across a man plotting to kill him, and turned the man into Deer. Moon turned four arguing women into useful plants. He turned five destructive brothers into Fire. Moon created Echo, he made sticks and stones stand still instead of attacking people, he turned a fish weir into Snoqualmie Falls. He did all this and more, and on returning home met for the first time his younger brother, Sun. Together, they decided how to light the world, and the people were satisfied with the changes Moon the Transformer had made. Rat, however, was not. He gnawed at the ladder the two sisters had created until it fell, becoming a stone outcropping which still stands near the town of North Bend.

The story of Star Child or Moon the Transformer, passed down through elite Snoqualmie families, would take hours to tell in its entirety. Like other Lushootseed stories, it is full of lessons about proper behavior, family connections, and relationships between the world's peoples, human and otherwise. (See also: "Some Tales of the Puget Sound Salish" and "Mythology of Southern Puget Sound".) Rarely offered explicitly, these lessons were hidden within the story, to be discovered by the listener. They form the heart of Huchoosedah.

Figures in the Landscape: Spirit Powers and Religious Traditions

For Lushootseed people, the world is full of spirits. Objects and places that appear inanimate, like rocks or weather, are known to be living beings with their own spirits, just like plans, animals, and people. These spirits have played a central role in the lives of Lushootseed people, providing the skills and knowledge necessary to survive and flourish.

The number of spirit powers in the world is limitless. Some are called career spirits, since they help with everyday work. Clam or Duck, for example, help in hunting, while others support the making of baskets or assist in gambling. Loon and Grizzly were among the spirits for warriors, while Wolf and Thunder boosted the careers of undertakers and orators respectively, and humanlike beings provided wealth. In addition to career spirits, curing spirits like Otter, Kingfisher, and a giant horned serpent could be obtained by men and women destined to become doctors.

To obtain spirit powers, young people underwent great sacrifices. Gweqwultsah, or Aunt Susie Sampson Peter, received her power in the 1870s. Eighty years later, she told her story, which was translated by Upper Skagit elder Vi (Taqsheblu) Hilbert and includes comments in parentheses from Gweqwultsah's son Martin Sampson:

My father made life very arduous for me because he was an Indian Doctor. He said to me "It doesn't matter that you are merely a woman, you shall become an Indian Doctor (in keeping with the prominence of your family ancestors).

You will abstain from putting food in your mouth. You will not eat much." So that is what I did. A little bit of bread was given to me, a small portion. It would be measured according to how long my throat was. It would have to be enough to satisfy my stomach. By this regime I was trained. Also, dried salmon would be cut off and measured (along my throat). [Her father said] "Just so much, just enough, will serve to keep you appeased (while training)."

I did not balk. I was maturing enough to understand. I am not sure of my age, however old I was. Maybe I was ten years old at that time. Never once did I come crying to my mother. When the West Wind blew, I was told, "Take off your clothes and run (as fast as you can). You need only to keep on your small undergarment. Alright, you go, run upriver." I did not pout or fuss (though I hesitated). Nonetheless, I took off my outer dress and I ran.

I removed my skirt, placed it beside the river, weighted it down with a rock, and I swam out into the current, away from shore. Out in the stream I floated in the pitch black night. I was not afraid. Nothing was allowed to scare me. So, that is how I found this particular power which always helps me, even as I grow older. Even now sustaining me is this doctoring power.

In her story, Gweqwultsah never mentions what her spirit power was. Indeed, the spirit powers were forces to be reckoned with. Relations with them were governed by strict rules, and they could never be fully understood by mortals; as one elder has said, spirits "wiggle away from your mind like a snake." It was dangerous to talk specifically about one's spirit power, and rude to ask about another person's. Disrespecting the spirit powers could lead to bad luck, illness, and even death.

Spirit powers were most evident during the ceremonies held in December and January, when the spirits visited Lushootseed towns and assisted in the rituals that bound communities together. In the longhouses, individuals performed the Winter Dance, releasing their spirit powers through expressive movements and songs. Naming was also done during this time, with ancient family names bestowed upon younger generations as a link between the past and the future. The ceremony of the Power Boards used carved and painted plaques to cleanse the house and the people present. The Spirit Canoe ceremony, in which doctors from several communities came together to perform a journey to the Land of the Dead to retrieve the souls of ill people, was the most important ritual of all. Along with storytelling, feasting, and giving of gifts, these ceremonies and the spirit powers that made them possible kept Huchoosedah alive.

Circling through the Seasons: Gathering Wealth from Land, River, and Sea

The Lushootseed peoples had many things to be thankful for. The Puget Sound region's shorelines, rivers, prairies, forests, and mountain slopes were rich with resources provided by the spirits so that the people might live.

Each year, Lushootseed people moved through their territories, setting up temporary camps to collect the wealth of land, sea, and river. In late January, they gathered along riverbanks for the first runs of spring salmon, and took large rakes to the shore to comb herring out of the surf. Early spring saw men carving new canoes for the summer. By May, salmonberry sprouts and other greens complemented last season's dried salmon eggs. Men began hunting deer and elk, while women gathered camas and clams from prairies and beaches owned by important families. In early summer, steelhead appeared in the rivers and berries appeared in the forests, while tiger lilies and wild carrots provided roots from beds passed on from mother to daughter. As summer progressed, runs of dog, silver, and king salmon crowded into the rivers to be caught by the thousands, while tart huckleberries ripened on upland slopes. Fall was the time for snaring ducks in aerial nets stretched between tall poles, for hunting deer and elk, and for catching smelt on Puget Sound. By November, most of the gathering was complete, and if it had been a good year, the people would have enough food to last through the winter. And as the spirits began to arrive in the towns in December, the annual cycle began again.

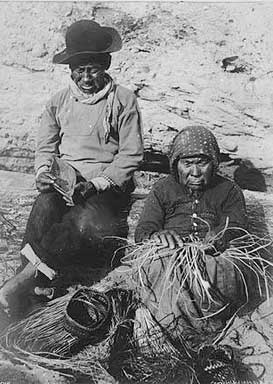

Beyond providing food, the landscape supported the rich Lushootseed material culture. Men with woodworking spirits used cedar to create planks and posts for houses, or to make one of six styles of canoe. (See also: "Adze, canoe, and house types of the Northwest coast".) Women used cedar bark to create decorated watertight baskets and waterproof clothing, and combined mountain goat wool, dog hair, and fireweed fluff to weave elegant blankets. (See also: "The Dog's Hair Blankets of the Coast Salish".) These fine arts drew on the spiritual powers of their makers and were expressions of discipline, expertise, spirit power, and good taste.

While Lushootseed people knew the spirits were the ultimate source of the land's abundance, they also played a large role in shaping the landscape. Far from "noble savages" leaving no trace on the "wilderness," Lushootseed people were environmental managers, transforming their world through their own ecological knowledge. Each year, for example, prairies were burned to renew the bulbs that grew there and to keep the forest at bay. Fishing technology was also a complex mix of science and art. Snuqualmi Jim described in the 1910s the construction and use of a fish weir:

Several sets of alder wood poles were set up tripod fashion across a river or creek where the water was quite shallow. The whole stream was fenced off with willow staves about eight feet long and one to two inches thick, stuck side by side in the river bed and lashed together with string. The row of willow sticks was fastened to the tripods, which were held together by a long pole. The water came to half the height of the willow sticks. Each tripod had a platform above the water which was about six feet square. The fisherman stood on this holding a long pole with a dip net about four or five feet long at the end. In coming up the river, the salmon were held back by the fence and the water at the trap would be full of fish. The men on the platforms took the salmon out of the water with their dip nets and clubbed them to death... Such a weir was called stukwalukw.

While weirs and other fishing technologies were designed to maximize the number of salmon caught, Lushootseed people knew to manage the resource. They left enough salmon to spawn, and ceremonies like the First Salmon, in which the bones of the first fish caught were returned to the water, ensured good relations between the Human People and the Salmon People. (See also: "A Further Analysis of the First Salmon Ceremony" and Jay Miller's essay "Salmon, the Lifegiving Gift".) This combination of practical and spiritual knowledge is at the heart of Huchoosedah.

Weaving a Life Together: Body, House, Community, Cosmos

The house was the center of Lushootseed community. These cedar structures could reach five hundred feet in length and housed several families, each with their own fire hearth sending smoke up a hole in the roof. More than simply shelter, Lushootseed houses symbolized the people's bodies, their prized canoes, and their world as a whole. The way Lushootseed people talked about their houses revealed these connections. A house's frame was seen as a body on its hands and knees, with the front of the house being called the face. Similar words were used for human skin, house walls, canoe hulls, and the edge of the world, while the roof ridge of a house was imagined as a spine, a river, and the Milky Way. Cedar posts holding up the roof, painted or carved with the power spirits of the leading family, were described both as human limbs and as pillars supporting the sky. Within this universe, cleaning a house, bailing a canoe, and curing an illness all were ways to set the world right.

Lushootseed houses also reflected relationships among people. The owners of the house, who led most day-to-day and ceremonial tasks, had their fire in a front corner away from doorway drafts. Common people had hearths along the sides and back, while slaves, captured from neighboring communities, found space where they could. (See also: "Slavery Among the Indians of Northwest America", PNQ 9:277-283.) In short, where a person sat in the house reflected where they sat in Lushootseed society.

Beyond the house, Lushootseed people organized themselves into autonomous towns, in contrast to the large tribes elsewhere. Far from isolated, these towns were linked through trade and marriage to other communities in Lushootseed territory and beyond. While conflict sometimes erupted between towns, intimate connections ensured a sharing of resources between neighboring communities. One of the most important traditions for maintaining these connections was the Sgwigwi, a word that simply means "inviting," and corresponds to the more familiar term potlatch, in which wealthy people displayed their social status by sharing their wealth with others.

Gram Ruth Sehome Shelton or Siastenu, a Tulalip elder, recalled the Sgwigwi in a 1950s interview:

They used to give potlatch every fall when there's plenty of everything. Plenty of ducks and plenty of salmon. Cause everything was plentiful in those days. Lost of deer, lots of ducks, lots of salmon, camas. Anything what the other tribe got, well they'll bring it to this potlatch to feed the people. Well, they'll all go home. Well, maybe here next fall, the other tribes will give a potlatch, and he'll do the same. That's the way the old people was. In the early days, that's the way they did this potlatch because white people thought that was very foolish of giving all what he's got. But keep up the poor, that's what this is for. Keep up the poor. That's the end of it.

In the Lushootseed language, there is no word for exclusion. Indeed, public displays of generosity were the most important way for families to mark an important occasion like a birth or death, to compete for social status, and to take responsibility for the well being of others.

Sgwigwi also provided an opportunity to participate in Slahal, the Bone Game. A highly competitive sport, Slahal matches could last for hours or days. The following is a description of Slahal by Skagit elder Martin Sampson:

It is usually played outdoors in the summer time. The people who want to play this game line up in teams facing each other. They sit on the ground. Each side chooses a leader. He is usually the owner of the two pairs of deer bones that are used in the game. One bone is marked with...black bands around it and one is plain. The objective is to guess in which hand the plain bone is hidden. There are ten tally sticks plus one which is called the "kick" stick.

Before the game begins, each side collects and records money in equal amounts for each side. This will be the pot that the winning side divides at the end of the game.

To decide which team starts the game, the leader who guesses the plain unmarked bone twice wins the kick stick for his team. He then starts the game by leading the group as they sing his song. He indicates two people who will hold the two pairs of bones. They shield their hands from view as they decide in which hand to hold the plain bone. The song is accompanied by a drumbeat. Sticks are pounded on boards lying on the ground in front of the players.

The leader on the opposite team now tries to guess in which hand the unmarked bones are. Each time he guesses incorrectly he must throw one of his tally sticks to the opposition. When the leader has guessed both of the unmarked bones, they are thrown to his team.

He chooses two players to hold the bones and then leads his group as they sing his song. The game is over when one team has lost all of the tally sticks to the other side.

In addition to being an exciting game, Slahal allowed members of neighboring towns to experience the force of the other players' spirit powers, who helped them in the game. Whether playing Slahal, participating in Sgwigwi, or taking part in other public events, guests usually sat in the direction of their home, making the Slahal field or the interior of a house a "map" of the larger world. The bodies of participants expressed the order of the Lushootseed cosmos, linking body, house, community, and world according to the people's Huchoosedah.

The World Changes: The Coming of Europeans and Americans

Europeans began arriving in Puget Sound in 1792, when British explorer George Vancouver sailed into the inland sea looking for a water passage across the continent. (See also: "Vancouver and the Indians of Puget Sound", PNQ 51:1-12.) Fur traders came over the next several decades, bringing with them new trade goods which were incorporated into day-to-day Lushootseed life. The newcomers also brought with them diseases like smallpox and measles, which swept through Lushootseed towns, sometimes killing two thirds of the people. Recurring raids by the Lekwiltok Kwakwaka'wakw, Haida, Stikine Tlingit (See also: Jay Miller's essay "Alaskan Tlingit and Tsimshian",) and other northern peoples also impacted Puget Sound Native communities. (See also: "Notes and Documents: Defending Puget Sound against the Northern Indians", PNQ 36:69-78.) Together, these changes presented many challenges for early nineteenth-century Lushootseed leaders like Kitsap of the Suquamish. (See also: "Documents: The Indian Chief Kitsap", PNQ 25:297-299, and "Documents: The Other View of Chief Kitsap", PNQ 25:299-301.)

Beginning in the 1850s, American settlers poured into Puget Sound country and put new pressures on Lushootseed communities. As elsewhere in North America, the settlers called for treaties to extinguish Native title to the land, and in 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens negotiated treaties with the Lushootseed people. (See also:"The Indian Treaty of Point No Point", PNQ 46:52-58.) Much confusion and distrust came from the treaties. Many Native leaders who signed them could not foresee their long-term effects, while others did not have the power to speak for those the government officials defined as a tribe. Since Lushootseed people organized themselves by town instead of by a tribe with a formal political leader, some communities were left out of the negotiations entirely. Still, perceptive treaty signers like Chief Seattle of the Duwamish and Suquamish laid the foundations that year for the rights of future generations. (See also: David Buerge's essay "Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons".)

As payments and benefits guaranteed in treaties were delayed or forgotten, armed conflict erupted. Some Lushootseed people took violent action against settlers, who they perceived as invaders, while settlers retaliated against Indians in their own, often lethal, ways. (See also: "Seattle's First Taste of Battle, 1856", PNQ 47:1-8.) Many Lushootseed villages were burned, and their residents forced to move to crowded reservations. On these reservations, individual Lushootseed towns would eventually form tribes in the true sense of the word - political entities with collective rights based on the treaties.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were difficult times for Lushootseed people. (See also: "The Present Status and Probable Future of the Indians of Puget Sound", PNQ 5:12-21.) As more settlers came to the region, Indian access to resources was made difficult or impossible. (See also: "Rights of the Puget Sound Indians to Game and Fish", PNQ 6:109-118.) Missionaries and government agents outlawed many of the ceremonies, and forced children to attend boarding schools where they were encouraged to forget their Huchoosedah. (See also: Carolyn Marr's essay "Assimilation Through Education: Indian Boarding Schools in the Pacific Northwest".) Lushootseed people trying to maintain traditional order in their communities often found themselves at odds with new American laws. (See also: "A Shaman-killing Case on Puget Sound, 1873-1874: American Law and Salish Culture", PNQ 86:17-23.) Meanwhile, poverty, disease, and loss of land to non-Indians made life on the reservations frustrating and often miserable. (See also: "Puyallup Indian Reservation", PNQ 19:202-205.)

However, despite the challenges faced by Lushootseed people, many adapted to their changing world by adopting and transforming new resources, traditions, and ways of life. Winter dancing and the other spirit ceremonies were augmented with new sources of spiritual power brought by the Christians, such as the Indian Shaker Church which combined Native and Christian elements in new, powerful ways. Meanwhile, Treaty Day festivals, canoe races (See also: "The Great Race of 1941: A Coast Salish Public Relations Coup", PNQ 89:127-133,) and Indian baseball leagues provided opportunities for Lushootseed people to maintain community, participate in traditional life, and present a positive image to their non-Indian neighbors. And a new generation of leaders put their boarding school education to work by creating new forms of tribal government. (See also: "The Swinomish People and Their State", PNQ 27:283-310.)

Work played an important part in Lushootseed survival during these times. Many Native people became part of the region's growing economy, with fishing, carpentry, logging, canoe ferrying, agricultural work, and basket making providing income for their families. Sometimes, this new work was an extension of skills provided by the spirits. A man with Woodpecker or Cedar power might work as a carpenter, while a berry picking spirit might help a young woman gather strawberries on a farm and a basket-making power could help make wares to sell to tourists. By the middle of the 20th century, Lushootseed identity had become a mix of the traditional and the new, the Native and the American.

Into the 21st Century: Survival and Adaptation

Today, there are nine reservations in Puget Sound country. From south to north, they are the Squaxin, Nisqually, Puyallup, Muckleshoot, Suquamish, Stillaguamish, Tulalip, Swinomish, and Upper Skagit. Three additional tribes, the Snoqualmie, Samish, and Skykomish, recently received recognition from the federal government, but do not have reservations. Two more tribes, the Duwamish and Steilacoom, are still working for federal recognition, which would give them access to treaty rights.

Lushootseed people today face many challenges. Traditional resources like cedar, salmon, and camas have been diminished by overharvesting and habitat destruction. Economic and educational opportunities on reservations are few, while Native people living off the reservation often face discrimination and the hardships of living away from their social networks. The Lushootseed language is only spoken fluently by a few elders, and Huchoosedah competes against television, pop music, and shopping malls.

But a renaissance is taking place in Lushootseed country. Indian communities in Puget Sound have used their political savvy to demand that treaty promises be honored. Their struggles for fishing rights, religious freedom, educational opportunity, and economic security have shaped the lives of everyone in the region. Meanwhile, new initiatives like casinos and hatcheries have spurred economic growth, and Lushootseed language programs and the revival of Winter Dancing have awakened Huchoosedah in the younger generations. In fact, this renaissance has been made possible in part by such new things as telephones, highways, and corporations. As many Lushootseed people say, survival does not mean living in the past. Instead, it means building new traditions to ensure the continuity of the community.

The story of Native American history in Puget Sound is one of trauma, transformation, and tradition. The world has changed in innumerable ways since the arrival of whites and other immigrants on these shores, yet those changes have not erased what it means to be Lushootseed, or the power of Huchoosedah in shaping lives. As the Lushootseed peoples enter the 21st century, they are doing so with a renewed vision of their place as the First People of Puget Sound country.

Bibliography

Brad Asher, Beyond the Reservation: Indians, Settlers, and the Law in Washington Territory, 1853-1889 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999).

Arthur Ballard, editor, Mythology of Southern Puget Sound: Legends Shared by Tribal Elders (North Bend: Snoqualmie Valley History Museum, 1999).

Dawn Bates, Thom Hess, and Vi Hilbert, Lushootseed Dictionary (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994).

Crisca Bierwert, Brushed by Cedar, Living by the River: Coast Salish Figures of Power (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999).

Crisca Bierwert, Lushootseed Texts: An Introduction to Puget Salish Narrative Aesthetics (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996).

Cecilia Svinth Carpenter, Where the Waters Begin: The Traditional Nisqually Indian History of Mount Rainier (Seattle: Northwest Interpretive Association, 1994).

George Pierre Castile, editor, The Indians of Puget Sound: The Notebooks of Myron Eels (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985).

J. A. Eckrom, Remembered Drums: A History of the Puget Sound Indian War (Walla Walla, WA: Pioneer Press Books, 1989).

Erna Gunther, Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981).

Hermann Haeberlin and Erna Gunther, The Indians of Puget Sound (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985).

Alexandra Harmon, Indians in the Making: Ethnic Relations and Indian Identities around Puget Sound (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

Vi Hilbert, Coyote and Rock and Other Lushootseed Stories (audio cassette) (New York: HarperCollins, 1992).

Vi Hilbert, editor, Haboo: Native American Stories from Puget Sound (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985).

Vi Hilbert and Crisca Bierwert, The Ways of the Lushootseed People: Ceremonies and Traditions of Northern Puget Sound Indians (Seattle: United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, 1980).

Katie Jennings, director, Huchoosedah: Traditions of the Heart (video recording) (Seattle: KCTS-9 and BBC Wales, 1995).

Jay Miller, Lushootseed Culture and the Shamanic Odyssey: An Anchored Radiance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

Jay Miller, Shamanic Odyssey: The Lushootseed Salish Journey to the Land of the Dead (Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press, 1988).

Susie Sampson Peter, Huchoosedah Gweqwultsah: The Wisdom of a Skagit Elder (Seattle: Lushootseed Press, 1995).

Gram Ruth Sehome Shelton, Huchoosedah Siastenu: The Wisdom of a Tulalip Edler (Seattle: Lushootseed Press, 1995).

The Suquamish Museum, The Eyes of Chief Seattle (Suquamish, WA: The Suquamish Museum, 1985).

Wayne Suttles, Coast Salish Essays (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1987).

Nile Thompson and Carolyn Marr, Crow's Shells: Artistic Basketry of Puget Sound (Seattle: Dushayay Publications, 1983).

Robin K. Wright, editor, A Time of Gathering: Native Heritage in Washington State (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991).

Study Questions

- What does the name "Lushootseed" mean? What other names have been used for the Native American peoples living around Puget Sound?

- What is Huchoosedah?

- Name three important Lushootseed ceremonies. What time of year do the ceremonies most often take place? Why?

- What role did spirit powers play in Lushootseed life?

- What is Sgwigwi?

- What kinds of natural resources made Lushootseed people wealthy in traditional times?

- What is Slahal?

- How did the coming of whites and other immigrants change Lushootseed life?

- What are some of the possible interpretations and teachings of the story of the Star Child, based on your personal reading of it?

- How did Lushootseed people shape their landscape?

- What is the relationship between the Lushootseed longhouse and the Lushootseed society and cosmos?

- How did wealthy Lushootseed people establish their position in society?

- What were some of the ways that a Lushootseed person in 1900 might pursue personal spiritual power?

- How have Lushootseed people adapted to the changes in their world over the past two centuries?

- What was the main unit of Lushootseed society before the arrival of Europeans and Americans? Why hasn't "tribe" always worked to describe Lushootseed social and political organization? At what point does "tribe" become useful way to describe Lushootseed organization?

- Why do you think the Lushootseed peoples have often been ignored by anthropologists and popular culture, especially when compared to "totem pole cultures" or "tipi cultures"?

Easier:

More Difficult:

About the Author

Coll-Peter Thrush was born in 1970, and grew up next door to the Muckleshoot Reservation southeast of Seattle. He holds a B.A. in Law & Diversity from Fairhaven College, the interdisciplinary wing of Western Washington University. His work has appeared in the Western Historical Quarterly, Pacific Northwest Forum, and Writing the Range: Race, Class, and Culture in the Women's West. Coll is currently a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Washington, where he is writing a dissertation on narratives of urban history and Indian history in the city of Seattle.