Richard V. "Dick" Correll (1904-1990), described as "one of the leading masters of printmaking in the West", was best known for his powerful black and white linoleum cuts, etchings and woodblock prints. For most of his life he earned a living as a commercial artist in the book publishing and advertising fields while producing a large body of fine art in his own time. His themes ranged from landscapes, animals and agricultural scenes, harbors and ships, and music and dance to those which reflected his lifelong concern with political and social issues. As one curator wrote, "the maturity of his technique, with its rich textures and dramatic contrasts, combines with a wide range of subject matter to produce a body of work of great warmth, power, and depth". Correll stated that, above all, he was a humanist.

"In art I am chiefly attracted by the synthesis of realism and design: That is, a humanitarian realism and an abstract-dramatic design - Each one to augment the other - an old combination of limitless possibilities."

Richard V. Correll painting a sign in Los Angeles, California, 1932

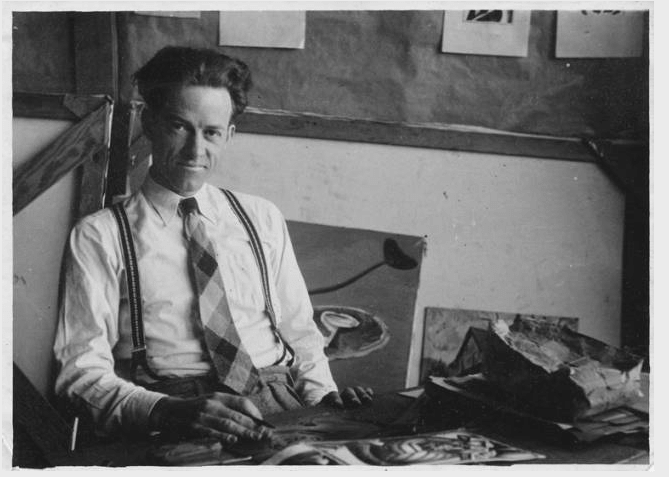

Richard V. Correll posing in an art studio, ca. 1935-1939

Born in Missouri 1904, Richard Correll spent most of his life in the three West Coast states, spending his early years in small farms or towns in Oregon and California. He absorbed his intellectual thirst – and the craft of fine woodworking - from his father, a lawyer, school teacher, master carpenter, and voracious reader, and the love of art and music from his mother, a musician trained at Oberlin. A natural artist from early childhood, by the age of four Dick was cutting perfect farm animals out of paper with his mother's sewing scissors. He was largely self-taught: "I combed the library of every place we moved to for reproductions and critical articles on artwork or artists. I'm a constant student." He also became sensitized to the environment early on through working in his family's small garden plots and farms and caring for the occasional family cow, horse or flock of chickens.

By the later 1920s the family had moved to Los Angeles. Dick's father and uncle began building houses there during the housing boom, with Dick doing the architectural drafting and his younger brother the electrical work. The two young men helped their father and brother with everything from basic construction to fine cabinetry. After the building boom collapsed with the Depression, Dick opened a couple of sign shops and did sign painting and calligraphy. He took a few art classes at what was then Chouinard Art Institute, but never attended as a matriculated student. He continued to sketch and draw on his own.

Dick's political thinking deepened with the Depression and seeing flocks of people uprooted by the Dust Bowl, hungry and homeless, stream into California. He began to see that art could be a vehicle to express ideas.

In 1933 Correll moved back to Oregon where he began creating prints for the Communist Party's weekly newspaper, the Voice of Action and contributing political cartoons to the New Masses. Correl's prints for the papers were distinguished by their detail and bold design. Correll moved to Seattle in 1935 and during this period, he also illustrated the Voice of Action's 1936 Northwest Labor Calendar. By the late 30s, Correll was selected to participate in the Federal Art Project of the Works Projects Administration (WPA). This recognition confirmed his decision to pursue art professionally, and gave him (and many other artists as well) an opportunity to earn their livings as fine artists, practicing artists for the first, and sometimes the only time in their lives. While working alongside such artists as Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, Faye Chong, Jules Twohy and Hannes Bok, Correll's work matured and his style crystallized.

Correll specialized in printmaking, primarily wood and linoleum block prints, but produced etchings and lithographs as well. In addition, he produced drawings, gouache paintings and two murals. Especially notable from Correll's WPA period is a suite of prints depicting the legendary American folk hero, Paul Bunyan. In one exhibition catalogue these were described to be "as large in spirit as their inspiration."

During the Seattle years, Correll was a founding member of the Washington Artists' Union. He married his wife Alice in 1938. He had several solo shows and exhibited widely in national juried group shows (Print Club of Philadelphia, the California Etcher's Society, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's Print Annual.) In 1939 his work was exhibited at the New York World's Fair. Many of the works from the WPA period are today in the collections of museums, universities, and public buildings and continue to be shown and circulated. His murals of Paul Bunyan remain in a high school in Bremerton, Washington.

Curator and fine print dealer M. Lee Stone writes, "In 1941 Correll and his wife moved to New York City where he remained for 11 years working in the commercial art field. New York's commercial and fine art scenes, however, were not without their difficulties. While commercial work paid decently, Correll always thought it a 'sorry thing' to use one's artistic abilities to sell products. His values were completely opposed to those of Madison Avenue, and this contradiction plagued him throughout his commercial career.

As America entered World War II, Correll, at 36, was too old for the draft. He joined the Civilian Defense Corps as an Air Raid Warden in the Greenwich Village area. He also did artwork for Civil Defense, producing dozens of pro bono flyers, banners, signs and posters for various causes." Daughter Leslie was born in 1944.

After joining the Artists League of America (ALA), an organization of progressive artists and sculptors "devoted to social, cultural, and economic interest of artists", Correll served as Publication Chair of the ALA News from 1943 on, and by 1946 was Editor. Membership in those years included Rockwell Kent, Lynd Ward, Jacob Lawrence and Moses Soyer. He exhibited regularly with ALA, and his linocut, "Air Raid Wardens" was included in the "Artists for Victory" travelling exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and 26 other venues in the USA and Canada.

Correll remarked, "New York was an especially exciting place for an artist during these years. Murals by the Mexican artists could be seen in the School for Social Research as well as in the Museum of Modern Art. Refugees from fascist persecution were bringing over the latest European art theories." George Grosz was teaching at the Art Students League. Correll knew Fritz Eichenberg, Robert Gwathmey and Miguel Covarrubias among others. Receiving serious attention in New York for the first time were works by Kathe Kollwitz, Edvard Munch, Miguel Covarrubias, Joseph Cornell, and the major collection of African sculpture owned by fellow ALA member Ladislas Segy. Fellow artists Norman Barr, Harry Roth and Abe Blashko were good friends of the Corrells.

In 1952 Dick had had enough of Madison Avenue and the family moved back to the West Coast, this time to San Francisco. Soon Dick joined the newly-formed Graphic Arts Workshop and Printmaker's Gallery of San Francisco, a dynamic group of progressive artist-activists who shared studio and exhibition space as well as the desire to serve the ideals of peace and social justice through their artwork. The GAW was then located in North Beach, which threw Dick into the vital art and cultural movement of the 50s. Through his lifelong membership in the Workshop he met and worked with many other noted San Francisco artists and muralists of his generation such as Emmy Lou Packard, Irving Fromer, Victor Arnautoff, William Wolff, Louise Gilbert, Pele de Lappe and Stanley Koppel. In 1954 he realized a lifelong dream of visiting México, the famous Taller de Gráfica Popular and the great works of Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros that had so influenced him and his generation.

Group of National Farm Workers Association members with picket sign created by Richard V. Correll, ca. 1960-1965

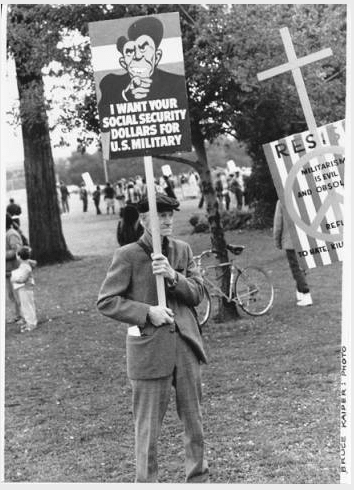

Richard V. Correll holding protest sign on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, 1983

On two occasions Correll participated with other artists in an attempt to form a union: in Washington with the Washington Artists Union and in New York City with the Artists League of America. Colleagues in the latter included Rockwell Kent, Lynd Ward, Philip Evergood, Ladislas Segy, Harry Gottlieb, Robert Gwathmey, Moses Sawyer, Art Young and Harry Sternberg. Correll served as the organization's Publications Chair and Editor of the A.L.A. News.

Correll's gentle and reserved demeanor was in sharp contrast to what San Francisco art critic Thomas Albright saw as the "remarkable boldness and strength" of his artwork. His themes often reflected his social conscience and he was attracted by heroic acts committed by everyday people in the struggle to achieve respect, freedom, and human rights. He marched with César Chávez and the United Farm Workers on their historic journey from Delano to Sacramento, contributed to and mounted the inaugural exhibition for the S.F. Afro-American Historical and Cultural Society, and created countless posters, leaflets, signs, and exhibits to civil rights, Native American, senior, labor, environmental, and world peace groups.

* Text excerpted courtesy of Correll Studios, www.richardvcorrell.com. Copyright © 2012, Correll Studios. All rights reserved.

"The Voice of Action was a radical labor newspaper that was published weekly in Seattle from March 1933 until October 1936. Although the Voice of Action was loyal to the Communist Party, this was rarely ever discussed. Instead, the general focus was on issues of forced labor, unemployment, labor politics, racism, the plight of the small farmer, and the crises of the poverty-stricken from starvation to forced eviction from their homes. Each issue of the Voice of Action was brimming with information in the form of much local, some national, and a little international news relating mainly to the aforementioned issues. This paper served as a source of news that could not be found in any other publications in this area during this period."1

Correll began contributing woodblock prints to the pages of Voice of Action on a weekly basis in 1933. One of several artists who contributed relief prints to issues of the newspaper, Correll's work stands out for its technical skill and strong design sense. 2

Years later, Correll recalled that coming up with ways to contain a lot of information in a small block print on a weekly basis helped him improve as an artist. The 1936 Northwest Labor History Calendar, illustrated by Correll, was published by the Voice of Action.2

View the Richard V. Correll digital collection at University of Washington Libraries Special Collections "Society and Culture collection" http://content.lib.washington.edu/socialweb/correll.html.