Everett Massacre of 1916 Collection

Essay: What happened that day in Everett

Sample Searches

Other Resources

STRIKES! Labor and Labor History in the Puget Sound

Industrial Workers of the World

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest

Tacoma Public Library Northwest Room, Unsettling Events database

Michigan State University Special Collections, American Radicalism Collection Digital Images

Everett Public Library: Northwest Digital Collections: The Everett Massacre

This collection, documenting labor's perspective of the 1916 Everett Massacre and its aftermath, currently holds 39 articles from the Seattle Union Record as well as 49 other items including pamphlets, fliers, hand- and typewritten works, postcards and a photograph.

Historical Background

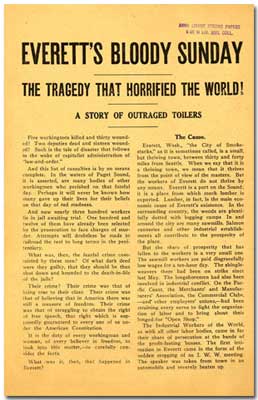

The November 5, 1916 Massacre was a culmination of labor trouble which had been brewing for 6 months. On May 1, 1916 the Everett Shingle Weavers Union went on strike. The Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) were not involved when the strike began. The strike was settled quickly, in favor of the mill owners, at all but one mill. This is when the I.W.W. became involved, and this is when the trouble began.

In 1916 the I.W.W. was a relatively new organization with Marxist beliefs, and a reputation for causing trouble. A 1909 I.W.W. strike in Spokane had cost the city over $250,000, a great deal of money at that time. Further, the first sentence in the I.W.W. preamble stated "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common." Thus, when the I.W.W. came to Everett, the establishment quickly became nervous.

When I.W.W. organizer and speaker James Rowan arrived in Everett on July 31, 1916, Everett became the home of the I.W.W.'s newest "Free-Speech Fight". This fight started relatively peacefully. Perhaps purposely, the I.W.W. speakers chose to speak at the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore, a corner where public speaking was illegal, although it was legal at other corners. At first, the speakers were merely arrested and released. Through a combination of idealism and realism (members were paid $1 by the union for every day they were in jail), the I.W.W. had little trouble finding volunteers to go to Everett and speak of free speech from Hewitt and Wetmore. The Everett jail was kept busy, and Snohomish County Sheriff Donald McRae quickly became frustrated. His next solution was to arrest the speakers, and upon their release, send them to Seattle, instructing them not to return to Everett. Additionally, a few small fires had been set in Everett, and although there was no indication the I.W.W. were involved (in fact, there were fewer fires in 1916 than there had been in 1915), the reputation of the I.W.W. led the mill-owners, the real power in Everett, to be afraid.

Image not in database

On August 19, 1916 the delicate balance changed, after an episode of violence at the Jamison Mill, the only mill left on strike. At the start of the shift on that day, the strike-breakers had beaten the picketers, and the police did not get involved, on the grounds that the mill was on private property. At the end of the shift, the picketers retaliated, but this time the police intervened. This inconsistency added fuel to the I.W.W.'s Free-Speech effort. A few days later Sheriff McRae closed the Everett I.W.W. office, apparently thinking this would drive the I.W.W. out of town, but this only served to further intensify the Free Speech Fight. Realizing that arrest alone did not serve as a deterrent to the speakers, the police now began beating the speakers the arrested. They ran I.W.W. members out of town, and prohibited entrance to town, merely for being members. The I.W.W. began bringing members to town in groups, but the police (enlisting the aid of citizen-deputies) beat the groups, as well. The worst of these beatings was on October 30, 1916. Forty-one I.W.W. members had come by ferry to Everett, to speak at Hewitt and Wetmore. The Sheriff and his deputies beat these men, took them to Beverly Park, and forced them to run through a gauntlet of 'law and order' officials, armed with clubs and whips. It was this horrific incident which caused the I.W.W. to organize a group of 300 men to travel to Everett on November 5 for a free-speech rally.

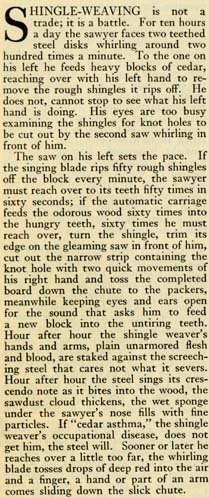

* Description of shingle weaving courtesy of the Sunset Publishing Corporation.

* Sunset, The Pacific Monthly, February 1917, Volume 38. The I.W.W. and the Golden Rule, Walter V. Woehlke; pp.16-18, 62-65

About the Database

This database represents a sample of the regional labor-related materials the University Libraries holds. The premier collections of materials concerning the Everett Massacre are held in public libraries such as the Everett Public Library, and in local historical societies and museums. This "seed" collection was funded through an LSTA grant from the Washington State Library Digital Imaging Initiative.

Materials for this database were selected from the Seattle Union Record and the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections Division holdings by Carla Rickerson and Theresa Mudrock. Materials were selected to provide in-depth labor coverage of both the event and of the following trial. Laura Lins served as project lead. Flatbed scanning was done on a Microtek ScanMaker 9600XL scanner by Laura Lins, Heather Johnson, Jane McFarlane and Julie Moede. Digital photography was done with an Olympus C-2000 Zoom camera by Laura Lins and Heather Johnson. Photoshopping, cataloging and arrangement of all items was done by Heather Johnson and Laura Lins, with assistance from Marsha Maguire and Allen Maberry. Research was done by Heather Johnson.